Monday, 23 May 2011

IMPORTANT GATHERING. Send smoke signals, e-mail etc.

OK folks, today is nothing but a full on, unbridled attempt to get you to come to the upcoming day gathering with Alastair McIntosh and myself, on July 6th, at the Chicken Shed (better than it sounds), just behind Schumacher College, Dartington, Devon. For any old students of the school, this and the Bardic summer school are absolutely designed to keep pushing forward of study of that which is fiery, mysterious, earthy, celestial, bawdy and true.

To book a place please ring 01364 653723 or send name, contact details and full amount made out to ‘the school of myth’ at Tregonning House, 27 Eastern rd, Ashburton, TQ13 7AP.

You are probably aware of Alastair through his many articles and at least three books, Soil and Soul, Hell and High Water, and Rekindling Community. This man is not a statistic wagging doom-monger, but an impassioned, lucid, occasionally furious, often hilarious, mystical and truly bright thinker. He is a poet, great prose writer and very decent teller of tales. He is also very busy which is WHY we are so lucky to have this day gathering with the man on some extremely deep and important issues, washed down with story, poetry and a good dollop of informed speculation. McIntosh's work is a genuine joy to read - so far past most attempts to handle ecological and psychological material it's not true.

I have come to his work very recently, and include a section of an essay i had just finished when i finally started to read him. And readers of his work will understand why i immediately loved it - he's pulling at many of the threads below, but very fleshed out and thought through - hence this gathering. This segment is part of a larger essay examining the diversive mythic impulses that live within us, regardless of how political correct we think we may be on the surface. It's also a caution against assumptions of leftish harmony - i like a bit of harmony when it arises naturally, but not at the entire expense of wildish discourse. Where this essay will lead in the end is an expansion on what the word harmony could mean...

Don't waste time being offended by the following, unless its worth consideration - i place myself entirely in its line of thought too.

.......

More than ever, the young folks I meet are often incredibly informed and activate as regards climate change. They are done with going on retreats into wild places, examining their navels, they are out there making a very real, very practical difference. I find this incredibly exciting. It makes me want to work harder. They have their ‘quest’, and it is the biggest one imaginable, to save the planet. However, the very oldest tools we have for crisis – stories - tell us that without an inner journey, that underworld knowledge, those hard scars from the Witch, then the outer life won’t quite align itself. This is where they come unstuck. This reflective work doesn’t offer the clear picture of the heroism of planet saving, it’s murkier, conflicted and hidden. To do with your own clogged oceans and toxic skies. No reward attached, no news report or twitter from your cave on the mountain.

There is a kind of smugness in us lefties that can be unpleasant. Our aspirations are seemingly just, but we still carry a subterranean trail of compressed ambitions and toothy animal drives with us – these can be harder to spot than those in the mainstream. We are more sophisticated at hiding, or we channel our grandiosity into wider causes. We pass the talking stick at meetings, speak ‘from the heart’ and always remember to do the recycling. We organise rallies and strut up and down our own ‘green’ towns and ignore actually going to that acutely depressed working class district five miles up the road. We leave all that stuff like soup kitchens and aid to the poor to the Christians we view as so spiritually unsophisticated. We funnel our kids through alternative schools for ludicrous fees that rarely prepare them for the intensities of modernity, and all the while do we think we are free of hierarchy, of judgement, of ambition? I think not. We’ve just stuck a rainbow coloured jumper over the armour.

We seem rightfully proud of our ecological credentials, our diligent harangues at local government and expensive organic produce. But this isn’t a sign of soulfulness, just an activated will. It’s crafty to suggest that these good deeds are of themselves spiritual but I don’t altogether buy it. Who exactly are they benefiting? Where are the poor, the marginal and the elderly in the mix? I see much of this hypocrisy in myself. It’s not enlightenment, just the same impulse system our parents had to keep up with the Jones’s, just moved a smidgeon to the left. It also has that whiff of ‘we’re all getting on Noah’s boat and the rest can drown’. It can be stiff with judgement though delivered with a queasy ‘namaste’.

At it’s worst it becomes a kind of profound self-absorption, something the New-Age recognises in its target audience. We read half a chapter of the Gnostic gospels over soya lattes and think we are ready to demolish the King James Bible.

Moving into a mythic perspective, which requires the interior world, saves us from continually trying to address the situation from linear, statistical, clock time. Attention to the eternal as well as the historical is a key insight into the inner situation around climate change. Stories give us images that have a genius that statistics and rallying do not. Statistics are bad for your health. They lower the immune system. Ted Hughes claimed that too much prose writing in neglect of poetry made him sick. Everything happening out there is somehow happening inside us too, so we as human animals could benefit from looking both ways. That soul work that maybe their parents did, or older siblings, that they are ‘done with’? could just be a key. The deeper story of ecology is wild mythology, and that realisation holds tremendous promise.

Are we addicted to harmony? This is very dangerous. Sign in at the door to collect your hemp year planner. Actually, scratch that, lets all ‘live in the moment’ with Eckhart Tolle and his enormous bank account. But, wherever you choose to live, or lifestyle you embrace, your inner figures – Warrior, Shrew, Queen, Hermit, will accompany you. They may have no intention of signing up for your politically correct lifestyle, and will burrow up into the most benign of situations, waving guns and bibles around. Well, maybe not a bible, but at least a book on raw food recipes. A mythological imagination would help us to comprehend what glides underneath our outwards compliance like hard eyed sharks. When life is truly regenerative it is a swarm of opinion and passions, not statistics and a kind of subliminal Puritanism. Harmony could be enjoyed when it arrives but not pursued. That doesn’t mean rough agreements aren’t needed – of course they are - but not so as they crush wild pockets of insight.

When people are anxious, when it seems some dark beast is coming to gobble our world, they have a tendency to look for something absolutely fixed, as a talisman against the strain of uncertainty that these challenges represent. Obsession with unified fronts, an assumed collective belief, harmony with a rod, often comes from fear. We feel overwhelmed and so are comforted by imagined absolutes. Even when we appear so very radical.

Terror of the end of time masks a true realisation that much is going to have to die – old habits and a childish dependency on the idea of harmony. As far as the gods go, right now is a Trickster moment we’re living in, more than Goddess time, Zeus time, or any other kind of time. We need to get clear on that.

The mythic is to do with polyphony – independent bursts of imagination arising in response to the mystery of existence – the doors to many temples are open. In other words, it’s promiscuous, allergic to dogma. The polyphonic is also the entrance to the ecstatic for many cultures –the colliding patterns of log drums and vocal chatter trip the intellect up until it falls headlong into spirit-time. The Trickster is always a polyphonic Bricoleur, a strategic heretic who conjures new art from this sometimes bruised assemblage of eruptions. A Bricoleur is an artist that assembles creation from things that wouldn’t normally be expected to fit together. It is an unusual beauty that emerges. We don’t hear polyphonic music on the radio, it’s tough on the ears.

When a room erupts with imaginative thoughts after the telling of a story it is present. Steamy, outraged and joyous opinions burst from the tongues of those present. And the Bricoluer starts to assemble a new boat on the messy sea. To aim always for harmony is to concrete up a fertile trail to the mythic. We lose many new insights. Myth, with its endless variations, comings and goings, erupting crisis’s and labyrinth like dilemmas, its wayward orchestrations of sudden brilliance, is the oldest, most inventive, and wonderfully anarchic vehicle we have for approaching today’s challenges.

But the answer will not come from one story but from many. A big problem will not be solved by a big answer.

As for myths place in this, It comes from wily Siberian folk tales, to Indian love stories, from the tacit whispers of the desert at night to great epics like this (Parzival). It will not be one beautifully held chord on a synthesiser but guttural and lucid eruptions from all corners of the myth-world. We, like shape-shifters, will have to contort to help create new dance steps from these implicit disclosures. It will not be a moment, but a slow residue of unruly insights. If we are lucky.

copyright Martin Shaw 2011

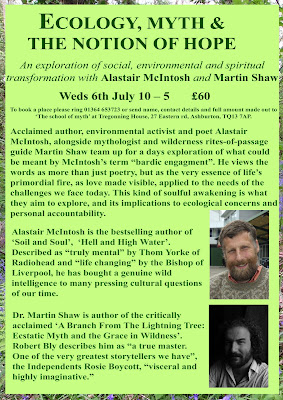

ECOLOGY, MYTH AND THE NOTION OF HOPE

Invoking the Bardic Tradition Today

An exploration of social, environmental and spiritual transformation with Alastair McIntosh and Martin Shaw

Wens 6th July 10 – 5 £60

Acclaimed author, environmental activist and poet Alastair McIntosh, alongside mythologist and wilderness rites-of-passage guide Martin Shaw team up for a days exploration of what could be meant by McIntosh’s term “bardic engagment”. He views the words as more than just poetry, but as the very essence of life’s primordial fire, as love made visible, applied to the needs of the challenges we face today. This kind of soulful awakening is what they aim to explore, and its implications to ecological concerns and personal accountability.

Shaw will start the gathering by telling an ancient Hebredian tale to give us a mythic perspective on theme, and offering insights as the day progresses. Alastair will lead a presentation, and his wider perception on the word ‘bardic’ to include the arts and spiritual practice. This will take much of the day. There will be both formal input and informal discussions and small groups. This promises to be an extremely rich and fruitful experience- do not miss this one!

Alastair McIntosh is the bestselling author of ‘Soil and Soul’, ‘Hell and High Water’. Described as “truly mental” by Thom Yorke of Radiohead and “life changing” by the Bishop of Liverpool, he has bought a genuine wild intelligence to many pressing cultural questions of our time.

Dr. Martin Shaw is author of the critically acclaimed ‘A Branch From The Lightning Tree: Ecstatic Myth and the Grace in Wildness’. Robert Bly describes him as “a true master. One of the very greatest storytellers we have”, the Independents Rosie Boycott, “visceral and highly imaginative.”

In more depth..... FROM ALASTAIR

We stand at a challenging time for movements that seek to advance social justice and environmental sustainability. Poverty remains ingrained even in the UK. Our country remains constantly at war. And the political progress that had been achieved on tackling major environmental issues like climate change has gone into reverse. People who don’t care have never had it so good. Those who retain the capacity for empathy, for altruism, and a concern for future generations worry, and with good cause. What has happened to the dream of an alternative society? Where stands the deep work for love, justice and peace?

In his book about climate change, Hell and High Water, described as a source “to quarry for inspiration” by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Alastair distinguishes between optimism and hope. He argues that while cause for optimism on the things that matter to us may have dimmed, we must never let go of hope. But what are the roots of hope? How do we get in touch with that fire of life that can feed inner meaning for our work even at times when it struggles outwardly?

From his campaigning work with land reform and environmental protection described in his earlier book, Soil and Soul, Alastair believes that outward political action on its own is not enough. We need that deeper source of hope if the oil in the lamp of life is neither to sell out nor burn out. One way into that, and one way of expressing it, is through bardic work. Alastair sees the bardic tradition as something that can be alive and working in us today. It is more than just poetry. It is the poetic fire of life, life as love made visible, applied to the needs of people and place in today’s world. It is that shift in consciousness, and the things that bring about that shift, which opens us to seeing the spiritual interiority and not just the physical or social exteriority of what concerns us.

During this day Martin Shaw will layout mythic themes, tell a story and convene the event. Most probably Alastair will start with a presentation looking at where we stand, and giving examples from his own work of what he means by bardic engagement. He uses this term to mean the arts and spirituality in general, and not just “poetry” as such. There will be space for both formal input and small group discussion.

Alastair McIntosh is best know for his work on Scottish land reform and helping to stop the proposed Isle of Harris superquarry, but underpinning these concerns has been a passion to convey the meanings of community, and how our work comes unstuck and egocentric if it is not grounded in the sacred. His books have variously been described as “world changing” by George Monbiot, “life-changing” by the Bishop of Liverpool, “inspirational” by Starhawk and “truly mental” by Thom Yorke of Radiohead. He is a Fellow of the Centre for Human Ecology, a visiting professor at the University of Strathclyde, and has guest lectured such unlikely groups as the Russian Academy of Science, WWF International, the World Council of Churches, Lothian and Borders Police and, for the past 15 years, on the Advanced Command & Staff Course at the UK Defence Academy.

To book a place please ring 01364 653723 or send name, contact details and full amount made out to ‘the school of myth’ at Tregonning House, 27 Eastern rd, Ashburton, TQ13 7AP.

You are probably aware of Alastair through his many articles and at least three books, Soil and Soul, Hell and High Water, and Rekindling Community. This man is not a statistic wagging doom-monger, but an impassioned, lucid, occasionally furious, often hilarious, mystical and truly bright thinker. He is a poet, great prose writer and very decent teller of tales. He is also very busy which is WHY we are so lucky to have this day gathering with the man on some extremely deep and important issues, washed down with story, poetry and a good dollop of informed speculation. McIntosh's work is a genuine joy to read - so far past most attempts to handle ecological and psychological material it's not true.

I have come to his work very recently, and include a section of an essay i had just finished when i finally started to read him. And readers of his work will understand why i immediately loved it - he's pulling at many of the threads below, but very fleshed out and thought through - hence this gathering. This segment is part of a larger essay examining the diversive mythic impulses that live within us, regardless of how political correct we think we may be on the surface. It's also a caution against assumptions of leftish harmony - i like a bit of harmony when it arises naturally, but not at the entire expense of wildish discourse. Where this essay will lead in the end is an expansion on what the word harmony could mean...

Don't waste time being offended by the following, unless its worth consideration - i place myself entirely in its line of thought too.

.......

More than ever, the young folks I meet are often incredibly informed and activate as regards climate change. They are done with going on retreats into wild places, examining their navels, they are out there making a very real, very practical difference. I find this incredibly exciting. It makes me want to work harder. They have their ‘quest’, and it is the biggest one imaginable, to save the planet. However, the very oldest tools we have for crisis – stories - tell us that without an inner journey, that underworld knowledge, those hard scars from the Witch, then the outer life won’t quite align itself. This is where they come unstuck. This reflective work doesn’t offer the clear picture of the heroism of planet saving, it’s murkier, conflicted and hidden. To do with your own clogged oceans and toxic skies. No reward attached, no news report or twitter from your cave on the mountain.

There is a kind of smugness in us lefties that can be unpleasant. Our aspirations are seemingly just, but we still carry a subterranean trail of compressed ambitions and toothy animal drives with us – these can be harder to spot than those in the mainstream. We are more sophisticated at hiding, or we channel our grandiosity into wider causes. We pass the talking stick at meetings, speak ‘from the heart’ and always remember to do the recycling. We organise rallies and strut up and down our own ‘green’ towns and ignore actually going to that acutely depressed working class district five miles up the road. We leave all that stuff like soup kitchens and aid to the poor to the Christians we view as so spiritually unsophisticated. We funnel our kids through alternative schools for ludicrous fees that rarely prepare them for the intensities of modernity, and all the while do we think we are free of hierarchy, of judgement, of ambition? I think not. We’ve just stuck a rainbow coloured jumper over the armour.

We seem rightfully proud of our ecological credentials, our diligent harangues at local government and expensive organic produce. But this isn’t a sign of soulfulness, just an activated will. It’s crafty to suggest that these good deeds are of themselves spiritual but I don’t altogether buy it. Who exactly are they benefiting? Where are the poor, the marginal and the elderly in the mix? I see much of this hypocrisy in myself. It’s not enlightenment, just the same impulse system our parents had to keep up with the Jones’s, just moved a smidgeon to the left. It also has that whiff of ‘we’re all getting on Noah’s boat and the rest can drown’. It can be stiff with judgement though delivered with a queasy ‘namaste’.

At it’s worst it becomes a kind of profound self-absorption, something the New-Age recognises in its target audience. We read half a chapter of the Gnostic gospels over soya lattes and think we are ready to demolish the King James Bible.

Moving into a mythic perspective, which requires the interior world, saves us from continually trying to address the situation from linear, statistical, clock time. Attention to the eternal as well as the historical is a key insight into the inner situation around climate change. Stories give us images that have a genius that statistics and rallying do not. Statistics are bad for your health. They lower the immune system. Ted Hughes claimed that too much prose writing in neglect of poetry made him sick. Everything happening out there is somehow happening inside us too, so we as human animals could benefit from looking both ways. That soul work that maybe their parents did, or older siblings, that they are ‘done with’? could just be a key. The deeper story of ecology is wild mythology, and that realisation holds tremendous promise.

Are we addicted to harmony? This is very dangerous. Sign in at the door to collect your hemp year planner. Actually, scratch that, lets all ‘live in the moment’ with Eckhart Tolle and his enormous bank account. But, wherever you choose to live, or lifestyle you embrace, your inner figures – Warrior, Shrew, Queen, Hermit, will accompany you. They may have no intention of signing up for your politically correct lifestyle, and will burrow up into the most benign of situations, waving guns and bibles around. Well, maybe not a bible, but at least a book on raw food recipes. A mythological imagination would help us to comprehend what glides underneath our outwards compliance like hard eyed sharks. When life is truly regenerative it is a swarm of opinion and passions, not statistics and a kind of subliminal Puritanism. Harmony could be enjoyed when it arrives but not pursued. That doesn’t mean rough agreements aren’t needed – of course they are - but not so as they crush wild pockets of insight.

When people are anxious, when it seems some dark beast is coming to gobble our world, they have a tendency to look for something absolutely fixed, as a talisman against the strain of uncertainty that these challenges represent. Obsession with unified fronts, an assumed collective belief, harmony with a rod, often comes from fear. We feel overwhelmed and so are comforted by imagined absolutes. Even when we appear so very radical.

Terror of the end of time masks a true realisation that much is going to have to die – old habits and a childish dependency on the idea of harmony. As far as the gods go, right now is a Trickster moment we’re living in, more than Goddess time, Zeus time, or any other kind of time. We need to get clear on that.

The mythic is to do with polyphony – independent bursts of imagination arising in response to the mystery of existence – the doors to many temples are open. In other words, it’s promiscuous, allergic to dogma. The polyphonic is also the entrance to the ecstatic for many cultures –the colliding patterns of log drums and vocal chatter trip the intellect up until it falls headlong into spirit-time. The Trickster is always a polyphonic Bricoleur, a strategic heretic who conjures new art from this sometimes bruised assemblage of eruptions. A Bricoleur is an artist that assembles creation from things that wouldn’t normally be expected to fit together. It is an unusual beauty that emerges. We don’t hear polyphonic music on the radio, it’s tough on the ears.

When a room erupts with imaginative thoughts after the telling of a story it is present. Steamy, outraged and joyous opinions burst from the tongues of those present. And the Bricoluer starts to assemble a new boat on the messy sea. To aim always for harmony is to concrete up a fertile trail to the mythic. We lose many new insights. Myth, with its endless variations, comings and goings, erupting crisis’s and labyrinth like dilemmas, its wayward orchestrations of sudden brilliance, is the oldest, most inventive, and wonderfully anarchic vehicle we have for approaching today’s challenges.

But the answer will not come from one story but from many. A big problem will not be solved by a big answer.

As for myths place in this, It comes from wily Siberian folk tales, to Indian love stories, from the tacit whispers of the desert at night to great epics like this (Parzival). It will not be one beautifully held chord on a synthesiser but guttural and lucid eruptions from all corners of the myth-world. We, like shape-shifters, will have to contort to help create new dance steps from these implicit disclosures. It will not be a moment, but a slow residue of unruly insights. If we are lucky.

copyright Martin Shaw 2011

ECOLOGY, MYTH AND THE NOTION OF HOPE

Invoking the Bardic Tradition Today

An exploration of social, environmental and spiritual transformation with Alastair McIntosh and Martin Shaw

Wens 6th July 10 – 5 £60

Acclaimed author, environmental activist and poet Alastair McIntosh, alongside mythologist and wilderness rites-of-passage guide Martin Shaw team up for a days exploration of what could be meant by McIntosh’s term “bardic engagment”. He views the words as more than just poetry, but as the very essence of life’s primordial fire, as love made visible, applied to the needs of the challenges we face today. This kind of soulful awakening is what they aim to explore, and its implications to ecological concerns and personal accountability.

Shaw will start the gathering by telling an ancient Hebredian tale to give us a mythic perspective on theme, and offering insights as the day progresses. Alastair will lead a presentation, and his wider perception on the word ‘bardic’ to include the arts and spiritual practice. This will take much of the day. There will be both formal input and informal discussions and small groups. This promises to be an extremely rich and fruitful experience- do not miss this one!

Alastair McIntosh is the bestselling author of ‘Soil and Soul’, ‘Hell and High Water’. Described as “truly mental” by Thom Yorke of Radiohead and “life changing” by the Bishop of Liverpool, he has bought a genuine wild intelligence to many pressing cultural questions of our time.

Dr. Martin Shaw is author of the critically acclaimed ‘A Branch From The Lightning Tree: Ecstatic Myth and the Grace in Wildness’. Robert Bly describes him as “a true master. One of the very greatest storytellers we have”, the Independents Rosie Boycott, “visceral and highly imaginative.”

In more depth..... FROM ALASTAIR

We stand at a challenging time for movements that seek to advance social justice and environmental sustainability. Poverty remains ingrained even in the UK. Our country remains constantly at war. And the political progress that had been achieved on tackling major environmental issues like climate change has gone into reverse. People who don’t care have never had it so good. Those who retain the capacity for empathy, for altruism, and a concern for future generations worry, and with good cause. What has happened to the dream of an alternative society? Where stands the deep work for love, justice and peace?

In his book about climate change, Hell and High Water, described as a source “to quarry for inspiration” by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Alastair distinguishes between optimism and hope. He argues that while cause for optimism on the things that matter to us may have dimmed, we must never let go of hope. But what are the roots of hope? How do we get in touch with that fire of life that can feed inner meaning for our work even at times when it struggles outwardly?

From his campaigning work with land reform and environmental protection described in his earlier book, Soil and Soul, Alastair believes that outward political action on its own is not enough. We need that deeper source of hope if the oil in the lamp of life is neither to sell out nor burn out. One way into that, and one way of expressing it, is through bardic work. Alastair sees the bardic tradition as something that can be alive and working in us today. It is more than just poetry. It is the poetic fire of life, life as love made visible, applied to the needs of people and place in today’s world. It is that shift in consciousness, and the things that bring about that shift, which opens us to seeing the spiritual interiority and not just the physical or social exteriority of what concerns us.

During this day Martin Shaw will layout mythic themes, tell a story and convene the event. Most probably Alastair will start with a presentation looking at where we stand, and giving examples from his own work of what he means by bardic engagement. He uses this term to mean the arts and spirituality in general, and not just “poetry” as such. There will be space for both formal input and small group discussion.

Alastair McIntosh is best know for his work on Scottish land reform and helping to stop the proposed Isle of Harris superquarry, but underpinning these concerns has been a passion to convey the meanings of community, and how our work comes unstuck and egocentric if it is not grounded in the sacred. His books have variously been described as “world changing” by George Monbiot, “life-changing” by the Bishop of Liverpool, “inspirational” by Starhawk and “truly mental” by Thom Yorke of Radiohead. He is a Fellow of the Centre for Human Ecology, a visiting professor at the University of Strathclyde, and has guest lectured such unlikely groups as the Russian Academy of Science, WWF International, the World Council of Churches, Lothian and Borders Police and, for the past 15 years, on the Advanced Command & Staff Course at the UK Defence Academy.

Wednesday, 18 May 2011

MAGICAL PRIVACY

Well, i know as a fact that the first boxes of Lightning Tree have left the printers this morning and are heading off to all sorts of destinations. It may take a little while longer via White Cloud, Amazon etc, but we are almost there.

I include two snaps above. One of myself, David Darling, poet laureate Lisa Starr and Coleman Barks mid-story at the first school of myth conference 'The Wild Hawk in the Lovers Garden', back in October 2009, and the great John Densmore and myself (with some kind of little fairy that i just met) outside the legendary McCabe's music store in Los Angeles last June. I Include them for this reason: June 24/25th Coleman, Lisa and myself will be in Norway at the Festival of Silence (they have obviously never heard us when the wine is poured) and teaching myth and poetry near the fjords in the following week, secondly John and I are about to do a collaboration of myth, poetry and percussion, somewhere, soon. Ok, that's enough, you can find the rest out yourselves, but it's all within the next 8 weeks.

Todays excerpt is from my continuing work on Parzival, and the notion of privacy. This may seem weird giving use of facebook etc, but i think most of us understand the balance between useful disclosure and the need to hold certain material back. This isn't a condemnation at large, but trying to hold these tensions within my own life. Magical privacy is holding that tension as the push towards networking grows in intensity. Many good things come out of speedy communication -Hermes is present -this is really a caution against a kind of playground popularity contest and its relationship to the focus so often on the 'outer' life.

HEY, please check out two flyers below todays post - for 'entering the bardic secret' summer school and 'ecology, myth and the notion of hope' with Alastair McIntosh. Please get in touch today if attending - places limited on both.

Magical Privacy: Getting the Lion Back

This Hermit’s hill has always been dear to me,

Also this hedgerow which keeps me hidden

Partially from the gaze of the wide horizon

Giacomo Leopardi

Mise mono ja nai

(‘this is not something we show to people’)

Zen saying

The possibility of low level fame through internet networking or implied media pressure seems to be provoking a kind of epileptic fit of friend making (i suspect i may have to change that phrase), groping madly towards the next addition to our wonderful tribe of complete strangers. It has hit a frantic nerve in modernity to be witnessed, visible, the centre of the wheel. A fame for no other reason than simply being here. The old saying goes, if you aren’t seen clearly by thirty people (a typical size of an old tribal group), then you will try and get the attention of thirty million to compensate. We are addicted to disclosure.

This phenomenon is a ghost memory of the mythic notion that we are designed to live a life of vocation, intensity and a little style. When that instinct gets caught in the slipstream of the need for busyness and the ‘next big thing’ it starts to distort, right down at the root. Our vocation becomes demonstrated by how many demands there are for out time, our intensity by how many new experiences we manage to cram in, and the style gets relegated to our six monthly up date on the latest phone. This is not the life that myth is hinting at.

At the beginning of this section I inserted the phrase “ Mise mono ja nai – this is not something we show people”. It originates from the Zen sentiment of not allowing visitors to a Zen training establishment – it’s simply not appropriate. There is more going on there than the desire to draw in more students and increase the temple coffers. Not everything is available, all the time. What a relief.

I remember as a young boy in bed hearing the front door close as my father strode out on one of his many late night walks. I would gaze up at my rain spattered window and wonder. I had no idea where he would go or when he would be back, criss-crossing the town we lived in and often ending up on the small streets that he had grown up on, twenty five years before. The dark allowed strange thoughts to get space in his head, answers to questions he barely knew he was asking. To my five year old mind the message this intimated was the night was an ally, that certain deep moods could not be met by other people, that part of our life ‘belongs to the wild darkness’ and that part remained private.

A church needs shadowed areas, dappled light, a balance between the lifting burst of the worship and the candle lit soulfulness of silence. We can accommodate the rousing togetherness of spirit, but seem far more unsure with the profound quiet of the soul. Brightly lit churches, meditation centres and yoga studios feature young, breezy teachers in recently swept rooms with no possibility of a crows muddy print on the linoleum. The sermons/sessions connect us to community, light, aspiration, charity works, our ‘highest good’. The problem is that the shadows we carry with us become indistinct, are made to wait in the car or the porn downloaded on our computer. The soul, as different to spirit, seems to be a network of shadows, like dozens of rooks over a winter field.

A window without curtains is a life always on display, the talk shows clamour for private material feels ultimately degraded, too much time by an open door is an insult to many sacred things.

The Dagara of Africa believe that when something from the inner world becomes public it is already in decline. Power at its most potent is private not public, tacit not explicit. Magical consciousness has to accommodate shadows or it has immediately made its potency finite. Some vital energy is drained from us when we disconnect from moon-like rhythms of visibility. Certain thoughts arc out like boomerangs and are not to accomplish themselves in speech – rather to hurtle back into the nourishing dark of our own quiet. We get damaged by too much daylight.

Not so long ago, I had the great honour of being the guest storyteller at the summer solstice celebrations of a north Californian tribe, The Miwok. Entering the longhouse at dusk was like stepping way back in time. The fire at its centre, the smoke billowing upwards, the gnarly columns of wood supporting the structure, the children’s eye’s mischievously peering over the flickers of the embers, it seemed a moment quite outside of normal time. The ritual dances ensued, lead by young boys and girls, secret words got spoken that helped the earth stagger onwards another day. We were all caught in some enormous prayer. But it was a prayer that engaged listening as much as speech.

I was at the back of the hut playing an earth drum for the ceremony. This is a crescent of earth that you stand upon whilst beating a pulse with a large, heavy staff. Above your head is the spirit hole, where at a certain point that only god can handle the spirits pour through from the Otherworld into this one. As the hours progressed and we moved deeper into the night it became clear that the Miwok’s relationship to speech and listening is very different to westerners. There was no enthusiastic rallying of the troops, no rousing sermon, rather the quietly spoken Ed, a man who spent large periods of time seemingly in contemplation of the wider picture, working, as we all were, at an entirely different pace to clock-time. When he spoke, the words were carefully chosen, conscious that raven, ocean, long grass and the thin legged Heron were also present to his language. There was tremendous space.

This was nothing to do with English being a second language or a lack of eloquence, quite the opposite, it was an eloquence of the wild, many openings to the living world within it. This way of being gave me time to loosen my psyche out into the wider landscape, it gave me time to settle into place. It was also a clue towards a way that the private and public can meet without this sense of diminishment – but it comes with a big price tag, stepping out of clock-time, the very tick tick tick of modernity.

On my home ground of Dartmoor there is a place I love to walk. I get up to Venford lake and stride out in the general direction of the Dart gorge, past the Bronze age settlement, and several old stone circles. My hope is always a glimpse of the tors –Bench Tor, Bel Tor, Yar Tor, and hidden, surrounded by trees on the other side of the river, Lucky Tor. The air is rich with oxygen and mossy scent. I have spent countless hours walking here alone and with loved ones, camping, leading wilderness fasts, praying. It begins with a panoramic view of the south moor, with just a hint of the bleaker north moor in the far distance, and then the slow path down to the river, with dappled shade from the oaks as you descend. After you pass the old Rowan on your left it gets steeper still, the gorge littered with fox holes and the air loaded with the rush of the rivers roar. You always begin the journey cold but by this point are laden down with jumpers tied around the waist and coats hidden under bushes to pick up on the way back.

I always look at the large incline ruefully, remembering the epic struggle of loading wheelbarrows full of rucksacks, lanterns, tents, supplies and wood and staggering up its ancient curves. After a four day fast just walking up with a staff can be brutal.

On the return journey I sometimes visit Buckfastleigh abbey, on the edge of the moor. Several times a day the monks enter the abbey from a hidden door, walk to the choir stalls with their habits over their heads, and, start to sing in Latin. No collection box, no sermon, no interaction with anyone present. The church is cool, shadowed, understated. But that sound – the chanting that has moved around and around that place, hollowing out some quiet entry point for the presence of holy feeling – that is extraordinary. Again, I move out of clock time. Again I see a hold way to hold privacy and the community. I believe that the circling call of the monks benefits the surrounding area, even for those that never visit the abbey, just in the way that the Dart endlessly churning through the moor towns does, its foam laden cadence splashing blessings on its rough bank.

The abbey is my re-entry point to the human village after alone time on the moor. It is spacious enough to accommodate my wild aura whilst touching my soul very deeply. I don’t worry about arguments about Church-ianty and wilderness, I just enter the truth of the sound. I love the mossy face of Christ. I seem to remember him heading out into the woods on more than one occasion. Born on the margins surrounded by animals, speaks a relentlessly strange doctrine, kicks the corporate bloodsuckers out of a sacred place, fasts in the wild, likes a drink, befriends hairy desert men and dark eyed prostitutes, goes to his death on a donkey, and, just when you think you’ve got him pinned down, starts showing up when he should be in the tomb. Disgraceful behaviour. Is there something we’re not getting here? If you want an image of Trickster behaviour, then you are looking at it. He is a dark fire.

Despite the push towards relentless, slightly glazed networking and rash levels of exposure, many people seem to want a deeper life. There is a dis-connect between what is bring enforced upon us through advertising, and for what we secretly hunger. In Coleman Bark’s work on Rumi he writes on what he calls “Lion Energy”

Each Lion is his own path, and he wants everyone to take total responsibility for himself or herself. The lion in a human being is almost without cowardice, and doesn’t long for, or expect, protection. The Lion is a Knight out in the wilderness by himself…being a lion is not fitting in, only to that which he generates and validates from within.

Coleman Barks. (Barks 1991 :pxi-xii)

The story of Parzival says that there is a Lion is us: a Lion that opens its vast jaw to the feasts of court, the tangles of the forest floor, the intrigues of culture, the thin road of the pilgrim. It has spirit-appetite. This Lion is independent; wilful, focused, sometimes harsh - it cannot be bought. It longs to wrestle with God. The Lion consumes emptiness and space with just the same vigour it settles on fresh meat. Rumi’s lion is in the business of saying no. He will eat desert and tundra, experience all kinds of heavy weather, but will not shoulder the trite, facile or domestic.

Martin Shaw copyright 2011

I include two snaps above. One of myself, David Darling, poet laureate Lisa Starr and Coleman Barks mid-story at the first school of myth conference 'The Wild Hawk in the Lovers Garden', back in October 2009, and the great John Densmore and myself (with some kind of little fairy that i just met) outside the legendary McCabe's music store in Los Angeles last June. I Include them for this reason: June 24/25th Coleman, Lisa and myself will be in Norway at the Festival of Silence (they have obviously never heard us when the wine is poured) and teaching myth and poetry near the fjords in the following week, secondly John and I are about to do a collaboration of myth, poetry and percussion, somewhere, soon. Ok, that's enough, you can find the rest out yourselves, but it's all within the next 8 weeks.

Todays excerpt is from my continuing work on Parzival, and the notion of privacy. This may seem weird giving use of facebook etc, but i think most of us understand the balance between useful disclosure and the need to hold certain material back. This isn't a condemnation at large, but trying to hold these tensions within my own life. Magical privacy is holding that tension as the push towards networking grows in intensity. Many good things come out of speedy communication -Hermes is present -this is really a caution against a kind of playground popularity contest and its relationship to the focus so often on the 'outer' life.

HEY, please check out two flyers below todays post - for 'entering the bardic secret' summer school and 'ecology, myth and the notion of hope' with Alastair McIntosh. Please get in touch today if attending - places limited on both.

Magical Privacy: Getting the Lion Back

This Hermit’s hill has always been dear to me,

Also this hedgerow which keeps me hidden

Partially from the gaze of the wide horizon

Giacomo Leopardi

Mise mono ja nai

(‘this is not something we show to people’)

Zen saying

The possibility of low level fame through internet networking or implied media pressure seems to be provoking a kind of epileptic fit of friend making (i suspect i may have to change that phrase), groping madly towards the next addition to our wonderful tribe of complete strangers. It has hit a frantic nerve in modernity to be witnessed, visible, the centre of the wheel. A fame for no other reason than simply being here. The old saying goes, if you aren’t seen clearly by thirty people (a typical size of an old tribal group), then you will try and get the attention of thirty million to compensate. We are addicted to disclosure.

This phenomenon is a ghost memory of the mythic notion that we are designed to live a life of vocation, intensity and a little style. When that instinct gets caught in the slipstream of the need for busyness and the ‘next big thing’ it starts to distort, right down at the root. Our vocation becomes demonstrated by how many demands there are for out time, our intensity by how many new experiences we manage to cram in, and the style gets relegated to our six monthly up date on the latest phone. This is not the life that myth is hinting at.

At the beginning of this section I inserted the phrase “ Mise mono ja nai – this is not something we show people”. It originates from the Zen sentiment of not allowing visitors to a Zen training establishment – it’s simply not appropriate. There is more going on there than the desire to draw in more students and increase the temple coffers. Not everything is available, all the time. What a relief.

I remember as a young boy in bed hearing the front door close as my father strode out on one of his many late night walks. I would gaze up at my rain spattered window and wonder. I had no idea where he would go or when he would be back, criss-crossing the town we lived in and often ending up on the small streets that he had grown up on, twenty five years before. The dark allowed strange thoughts to get space in his head, answers to questions he barely knew he was asking. To my five year old mind the message this intimated was the night was an ally, that certain deep moods could not be met by other people, that part of our life ‘belongs to the wild darkness’ and that part remained private.

A church needs shadowed areas, dappled light, a balance between the lifting burst of the worship and the candle lit soulfulness of silence. We can accommodate the rousing togetherness of spirit, but seem far more unsure with the profound quiet of the soul. Brightly lit churches, meditation centres and yoga studios feature young, breezy teachers in recently swept rooms with no possibility of a crows muddy print on the linoleum. The sermons/sessions connect us to community, light, aspiration, charity works, our ‘highest good’. The problem is that the shadows we carry with us become indistinct, are made to wait in the car or the porn downloaded on our computer. The soul, as different to spirit, seems to be a network of shadows, like dozens of rooks over a winter field.

A window without curtains is a life always on display, the talk shows clamour for private material feels ultimately degraded, too much time by an open door is an insult to many sacred things.

The Dagara of Africa believe that when something from the inner world becomes public it is already in decline. Power at its most potent is private not public, tacit not explicit. Magical consciousness has to accommodate shadows or it has immediately made its potency finite. Some vital energy is drained from us when we disconnect from moon-like rhythms of visibility. Certain thoughts arc out like boomerangs and are not to accomplish themselves in speech – rather to hurtle back into the nourishing dark of our own quiet. We get damaged by too much daylight.

Not so long ago, I had the great honour of being the guest storyteller at the summer solstice celebrations of a north Californian tribe, The Miwok. Entering the longhouse at dusk was like stepping way back in time. The fire at its centre, the smoke billowing upwards, the gnarly columns of wood supporting the structure, the children’s eye’s mischievously peering over the flickers of the embers, it seemed a moment quite outside of normal time. The ritual dances ensued, lead by young boys and girls, secret words got spoken that helped the earth stagger onwards another day. We were all caught in some enormous prayer. But it was a prayer that engaged listening as much as speech.

I was at the back of the hut playing an earth drum for the ceremony. This is a crescent of earth that you stand upon whilst beating a pulse with a large, heavy staff. Above your head is the spirit hole, where at a certain point that only god can handle the spirits pour through from the Otherworld into this one. As the hours progressed and we moved deeper into the night it became clear that the Miwok’s relationship to speech and listening is very different to westerners. There was no enthusiastic rallying of the troops, no rousing sermon, rather the quietly spoken Ed, a man who spent large periods of time seemingly in contemplation of the wider picture, working, as we all were, at an entirely different pace to clock-time. When he spoke, the words were carefully chosen, conscious that raven, ocean, long grass and the thin legged Heron were also present to his language. There was tremendous space.

This was nothing to do with English being a second language or a lack of eloquence, quite the opposite, it was an eloquence of the wild, many openings to the living world within it. This way of being gave me time to loosen my psyche out into the wider landscape, it gave me time to settle into place. It was also a clue towards a way that the private and public can meet without this sense of diminishment – but it comes with a big price tag, stepping out of clock-time, the very tick tick tick of modernity.

On my home ground of Dartmoor there is a place I love to walk. I get up to Venford lake and stride out in the general direction of the Dart gorge, past the Bronze age settlement, and several old stone circles. My hope is always a glimpse of the tors –Bench Tor, Bel Tor, Yar Tor, and hidden, surrounded by trees on the other side of the river, Lucky Tor. The air is rich with oxygen and mossy scent. I have spent countless hours walking here alone and with loved ones, camping, leading wilderness fasts, praying. It begins with a panoramic view of the south moor, with just a hint of the bleaker north moor in the far distance, and then the slow path down to the river, with dappled shade from the oaks as you descend. After you pass the old Rowan on your left it gets steeper still, the gorge littered with fox holes and the air loaded with the rush of the rivers roar. You always begin the journey cold but by this point are laden down with jumpers tied around the waist and coats hidden under bushes to pick up on the way back.

I always look at the large incline ruefully, remembering the epic struggle of loading wheelbarrows full of rucksacks, lanterns, tents, supplies and wood and staggering up its ancient curves. After a four day fast just walking up with a staff can be brutal.

On the return journey I sometimes visit Buckfastleigh abbey, on the edge of the moor. Several times a day the monks enter the abbey from a hidden door, walk to the choir stalls with their habits over their heads, and, start to sing in Latin. No collection box, no sermon, no interaction with anyone present. The church is cool, shadowed, understated. But that sound – the chanting that has moved around and around that place, hollowing out some quiet entry point for the presence of holy feeling – that is extraordinary. Again, I move out of clock time. Again I see a hold way to hold privacy and the community. I believe that the circling call of the monks benefits the surrounding area, even for those that never visit the abbey, just in the way that the Dart endlessly churning through the moor towns does, its foam laden cadence splashing blessings on its rough bank.

The abbey is my re-entry point to the human village after alone time on the moor. It is spacious enough to accommodate my wild aura whilst touching my soul very deeply. I don’t worry about arguments about Church-ianty and wilderness, I just enter the truth of the sound. I love the mossy face of Christ. I seem to remember him heading out into the woods on more than one occasion. Born on the margins surrounded by animals, speaks a relentlessly strange doctrine, kicks the corporate bloodsuckers out of a sacred place, fasts in the wild, likes a drink, befriends hairy desert men and dark eyed prostitutes, goes to his death on a donkey, and, just when you think you’ve got him pinned down, starts showing up when he should be in the tomb. Disgraceful behaviour. Is there something we’re not getting here? If you want an image of Trickster behaviour, then you are looking at it. He is a dark fire.

Despite the push towards relentless, slightly glazed networking and rash levels of exposure, many people seem to want a deeper life. There is a dis-connect between what is bring enforced upon us through advertising, and for what we secretly hunger. In Coleman Bark’s work on Rumi he writes on what he calls “Lion Energy”

Each Lion is his own path, and he wants everyone to take total responsibility for himself or herself. The lion in a human being is almost without cowardice, and doesn’t long for, or expect, protection. The Lion is a Knight out in the wilderness by himself…being a lion is not fitting in, only to that which he generates and validates from within.

Coleman Barks. (Barks 1991 :pxi-xii)

The story of Parzival says that there is a Lion is us: a Lion that opens its vast jaw to the feasts of court, the tangles of the forest floor, the intrigues of culture, the thin road of the pilgrim. It has spirit-appetite. This Lion is independent; wilful, focused, sometimes harsh - it cannot be bought. It longs to wrestle with God. The Lion consumes emptiness and space with just the same vigour it settles on fresh meat. Rumi’s lion is in the business of saying no. He will eat desert and tundra, experience all kinds of heavy weather, but will not shoulder the trite, facile or domestic.

Martin Shaw copyright 2011

Saturday, 14 May 2011

Thursday, 12 May 2011

THE SCHOOL AND THE LAND

Todays contribution is something entirely new - part of a book to come somewhere down the road. If you glance to your right of this column you will see a link to the school face book page. On it are several videos of me talking about both the Lightning Tree book and the school. If you enjoy them i would ask that you pass the links onto other folks. We rely entirely on goodwill, so this would be a tremendous help as we spread the word.

Come late Sept/early Oct UK Year program begins again - HERE ARE DATES: Wildwise indicates camping, Blytheswood residential.

Oct 15-16th Wildwise

Dec 2-4 Blytheswood

Feb 3-5 Blytheswood

April 27-29 Blytheswood

June 27-29th Wildwise

Although you can join programme at any point, deposit for the whole year - 250 pounds is required. So the deposit takes fifty pounds off the price of each weekend - paid in advance. This way you could say join in February, and complete course by attending first two weekends of next year. For more details ring 01364 653723 or

tina.schoolofmyth@yahoo.com (try there first i would suggest)

It is odd that in the growing Western preoccupation with organic food, yoga and un-feisty thoughts we often neglect myth as another kind of food – a literal soul food. Maybe we sense that its full fat, often barbecued and calorific content would create too much disturbance in the den. But It could be a crafty way of getting some protein into your internal eco-system without risking heart disease.

It was awareness of this kind of soul-poverty, a cultural deprivation, even within all of the material abundance many of us possess, that led to the forming of a hedge – school down here in Devon. The idea with a hedge school is quite literal – an Irish idea that you assemble some kind of rough structure against the side of a hedge and begin to teach underneath it from whatever skills you have. It’s all very simple, and comes from a time of tremendous hardship.

Many friends suggested this wasn’t a good idea, or to wait for some kind of government funding, or possibly an arts council grant. I do not compute this kind of thinking. No pirate could stomach its cautious implications, its lilly-livered, half-wish of an idea. Even In a county positively overflowing with spiritual sorts – and packed programmes on bodywork, psychology and vegetarian cookery there seemed little hope for a wayward, no qualification at the end, headlong immersion into the nature of myth, wilderness and rites-of-passage. And the lure? the sweet centre to get folks to sign up? At its centre was four days with an empty belly, headache and nightmares, glued to the side of a ghostly Welsh mountain in the pouring rain.

Well, it appeared my friends may be right. For the first year the school had three students. I was partially catering as well as teaching, running back and forth with plates of food. Cara was the real engine room of the kitchen, eyes weeping from chopped onions (well, that’s what she tells me). The next year was a big step upward – we now had four students. Big time. Any profit amounted to a six pack of cold beer and a packet of fish’n’chips after everyone had left on the Sunday night. I clearly remember the first time I had enough money left over to buy a book on the Monday morning. I still keep it close by.

The early years were intense. We’d rise at dawn, grab towels and walk in silence through a mile of forest down from our raggedy tent till we got to a small river. We always began the course in the depths of winter, just to increase its edge. We would go down backwards into the water, float to the very bottom, get a good soak of icy rapture, before back to fire making, cups of hot tea, and the days unfolding curriculum. There was absolutely no time off: myth, ritual, poetry and a little food, hard at it between 6am and 11pm. Much of the time was spent traversing gnotted forest, jumping into the ocean with wild flowers, chocolate and poetry for Mannanan Mac lir, or deep in the clutches of some esoteric old story. It seemed quite wonderful to all of us. We were a strange Fianna, following the moon trail of the bone white stag.

Next time round we had thirty folks and a waiting list. Were I to tell you of what was required to move it so dramatically in numbers it would require another book. The truth is that we were never size-ist. Were that Hedge school still three in number, no doubt I would still be there, sheltering from the rain, telling indecent jokes, drinking tea and teaching as best I can.

We have blessed beyond measure by the folks that become immediate family – like something from the old stories. Remember Jonny Bloor? – not only was he the schools very first student, he went on to become a right hand man: leader of music, general encourager and apprentice poet. In fact all three of the first years – Scott, David and Jonny, went onto play vital roles within the emerging school. Chris Salisbury the outdoorsman and storyteller, brought a wealth of practical forest knowledge, experience of the performative side of storytelling and a calm eye. Tim Russell the pirate philosopher with his Nart sagas and troubling insights. The women started to roll in too – Sue, Sam, Tina, Reba, Maggie, Ronnie and beyond. What a gift, a continual deepening. Storytellers, organizers, poets, gardeners, artists, they brought it all. We are adrift with cooks that play the banjo, mechanics that tell the epic of Gilgamesh, surgeons that have remembered they are really bandit queens, grief counsellors that have not stopped laughing, life coaches that have not stopped weeping. We have been buffeted by weather, death, illness, financial scrapes, wayward leadership (ahem), but, for anyone dreaming of a more complicated, unwieldy life we are right there. Not an arts grant of funding application in sight. Why not come find us?

And what of Dartmoor, the seat of the school? Dartmoor has been submerged in ocean, a tropical island, a red wood forest, and over time, an interlaced consortium of wild and domestic interaction. Its surface is highly ridged with human impressions. Go down to Merrivale just before dawn in May and you’ll see a double row of stones near the road side. As it gets lighter you will see that the stones point devotionally to the star cluster of the Pleiades rising up from the east. These jagged eruptions guided the seeding and the harvesting of precious crop, five thousand years past.

It’s not hard to detect the remnants of corn-drying barns, longhouses, the banked up reaves which marked the fields, the cromlech tomb of Spinster’s Moor, the stone circles of Scorhill and Grey Wethers, the standing stone of Drizzlecombe, then down through the dreaming into the hillfort at Hembury, then Lydford and its Anglo-Saxon patterning that still lives under its street design today, the clapper bridges and stannery routes, or old Brentor church - wrenched and groaned into life atop a volcanic outcrop in the 12th century, caught on a ley line that stretches from Cornwall to East Anglia.

Most of the tors were originally people: Bowerman out hunting with his dogs, interrupted a coven of witches who promptly turned him and the hounds into stone. Vixiana the Witch was hurled into a swamp and the grandparents say that the grassy bristles sticking out are from her hairy chin, just feet beneath the surface.

There is barely a copse, stretch of lane, or fecund outcrop that lacks a name and a story. Three hundred and sixty five square miles of intrigue and layered myth. But even Dartmoor, seemingly so permanent, is a shape-shifter, just like the story’s are. The red-ochre soils we enjoy here today are the remnants of what was once a kind of desert sand, carried by flash floods down from the highest points of the moor. Our chalk is a reminder of when the moor was completely covered by sea and was covered in limestone.

It has been cultivated, abandoned, mined, regenerated, feared, shorn bald of its tree crest. From a human eye it has been both cramped and lonely, fertile and barren. It carries a word-hoard of story, is a vascular intermingling of animals intelligence’s. It is its own wild consciousness, it’s own fluid mythology, whatever shape a particular millennium places upon it. These are just temporary bumps along the way, little snippets of clock time pecking at its great, eternal tumps.

Copyright Martin Shaw 2011

Come late Sept/early Oct UK Year program begins again - HERE ARE DATES: Wildwise indicates camping, Blytheswood residential.

Oct 15-16th Wildwise

Dec 2-4 Blytheswood

Feb 3-5 Blytheswood

April 27-29 Blytheswood

June 27-29th Wildwise

Although you can join programme at any point, deposit for the whole year - 250 pounds is required. So the deposit takes fifty pounds off the price of each weekend - paid in advance. This way you could say join in February, and complete course by attending first two weekends of next year. For more details ring 01364 653723 or

tina.schoolofmyth@yahoo.com (try there first i would suggest)

It is odd that in the growing Western preoccupation with organic food, yoga and un-feisty thoughts we often neglect myth as another kind of food – a literal soul food. Maybe we sense that its full fat, often barbecued and calorific content would create too much disturbance in the den. But It could be a crafty way of getting some protein into your internal eco-system without risking heart disease.

It was awareness of this kind of soul-poverty, a cultural deprivation, even within all of the material abundance many of us possess, that led to the forming of a hedge – school down here in Devon. The idea with a hedge school is quite literal – an Irish idea that you assemble some kind of rough structure against the side of a hedge and begin to teach underneath it from whatever skills you have. It’s all very simple, and comes from a time of tremendous hardship.

Many friends suggested this wasn’t a good idea, or to wait for some kind of government funding, or possibly an arts council grant. I do not compute this kind of thinking. No pirate could stomach its cautious implications, its lilly-livered, half-wish of an idea. Even In a county positively overflowing with spiritual sorts – and packed programmes on bodywork, psychology and vegetarian cookery there seemed little hope for a wayward, no qualification at the end, headlong immersion into the nature of myth, wilderness and rites-of-passage. And the lure? the sweet centre to get folks to sign up? At its centre was four days with an empty belly, headache and nightmares, glued to the side of a ghostly Welsh mountain in the pouring rain.

Well, it appeared my friends may be right. For the first year the school had three students. I was partially catering as well as teaching, running back and forth with plates of food. Cara was the real engine room of the kitchen, eyes weeping from chopped onions (well, that’s what she tells me). The next year was a big step upward – we now had four students. Big time. Any profit amounted to a six pack of cold beer and a packet of fish’n’chips after everyone had left on the Sunday night. I clearly remember the first time I had enough money left over to buy a book on the Monday morning. I still keep it close by.

The early years were intense. We’d rise at dawn, grab towels and walk in silence through a mile of forest down from our raggedy tent till we got to a small river. We always began the course in the depths of winter, just to increase its edge. We would go down backwards into the water, float to the very bottom, get a good soak of icy rapture, before back to fire making, cups of hot tea, and the days unfolding curriculum. There was absolutely no time off: myth, ritual, poetry and a little food, hard at it between 6am and 11pm. Much of the time was spent traversing gnotted forest, jumping into the ocean with wild flowers, chocolate and poetry for Mannanan Mac lir, or deep in the clutches of some esoteric old story. It seemed quite wonderful to all of us. We were a strange Fianna, following the moon trail of the bone white stag.

Next time round we had thirty folks and a waiting list. Were I to tell you of what was required to move it so dramatically in numbers it would require another book. The truth is that we were never size-ist. Were that Hedge school still three in number, no doubt I would still be there, sheltering from the rain, telling indecent jokes, drinking tea and teaching as best I can.

We have blessed beyond measure by the folks that become immediate family – like something from the old stories. Remember Jonny Bloor? – not only was he the schools very first student, he went on to become a right hand man: leader of music, general encourager and apprentice poet. In fact all three of the first years – Scott, David and Jonny, went onto play vital roles within the emerging school. Chris Salisbury the outdoorsman and storyteller, brought a wealth of practical forest knowledge, experience of the performative side of storytelling and a calm eye. Tim Russell the pirate philosopher with his Nart sagas and troubling insights. The women started to roll in too – Sue, Sam, Tina, Reba, Maggie, Ronnie and beyond. What a gift, a continual deepening. Storytellers, organizers, poets, gardeners, artists, they brought it all. We are adrift with cooks that play the banjo, mechanics that tell the epic of Gilgamesh, surgeons that have remembered they are really bandit queens, grief counsellors that have not stopped laughing, life coaches that have not stopped weeping. We have been buffeted by weather, death, illness, financial scrapes, wayward leadership (ahem), but, for anyone dreaming of a more complicated, unwieldy life we are right there. Not an arts grant of funding application in sight. Why not come find us?

And what of Dartmoor, the seat of the school? Dartmoor has been submerged in ocean, a tropical island, a red wood forest, and over time, an interlaced consortium of wild and domestic interaction. Its surface is highly ridged with human impressions. Go down to Merrivale just before dawn in May and you’ll see a double row of stones near the road side. As it gets lighter you will see that the stones point devotionally to the star cluster of the Pleiades rising up from the east. These jagged eruptions guided the seeding and the harvesting of precious crop, five thousand years past.

It’s not hard to detect the remnants of corn-drying barns, longhouses, the banked up reaves which marked the fields, the cromlech tomb of Spinster’s Moor, the stone circles of Scorhill and Grey Wethers, the standing stone of Drizzlecombe, then down through the dreaming into the hillfort at Hembury, then Lydford and its Anglo-Saxon patterning that still lives under its street design today, the clapper bridges and stannery routes, or old Brentor church - wrenched and groaned into life atop a volcanic outcrop in the 12th century, caught on a ley line that stretches from Cornwall to East Anglia.

Most of the tors were originally people: Bowerman out hunting with his dogs, interrupted a coven of witches who promptly turned him and the hounds into stone. Vixiana the Witch was hurled into a swamp and the grandparents say that the grassy bristles sticking out are from her hairy chin, just feet beneath the surface.

There is barely a copse, stretch of lane, or fecund outcrop that lacks a name and a story. Three hundred and sixty five square miles of intrigue and layered myth. But even Dartmoor, seemingly so permanent, is a shape-shifter, just like the story’s are. The red-ochre soils we enjoy here today are the remnants of what was once a kind of desert sand, carried by flash floods down from the highest points of the moor. Our chalk is a reminder of when the moor was completely covered by sea and was covered in limestone.

It has been cultivated, abandoned, mined, regenerated, feared, shorn bald of its tree crest. From a human eye it has been both cramped and lonely, fertile and barren. It carries a word-hoard of story, is a vascular intermingling of animals intelligence’s. It is its own wild consciousness, it’s own fluid mythology, whatever shape a particular millennium places upon it. These are just temporary bumps along the way, little snippets of clock time pecking at its great, eternal tumps.

Copyright Martin Shaw 2011

Thursday, 5 May 2011

LIGHTNING TALK

Half way through the Tagorefest. Good night in the Great Hall on tuesday evening - packed, and lots of Rumi from Duncan MacIntosh and choral and ecstatic chants from Chloe Goodchild. I was telling stories - 'The She-Wolf in the Midnight Orchard' or as many call it, 'The Handless Maiden'. I can't tell you how much i loathe that title.This woman is a lupine surge of holy intensity. I missed and continue to miss Coleman but read a little Rumi on his behalf - he is recovering well and we hope to be on the road in Norway by the end of next month. Back there today for Andrew Motion and Simon Armitage - do you have his translation of Gawain and the Green Knight? Hope so.

Here's another bit of taster from 'A Branch From The Lightning Tree'. The context is some reflection from myself on some years i spent living outdoors and its relationship to the bigger wilderness fasts i was engaged with. Please surprise White Cloud Press by pre-ordering! They aim to have it on the streets in about three-four weeks.

# please note: when i talk about storytellers below i am not just referring to writers and tellers but a much wider, stranger group - a storycarrier, rather than just teller. We are all in this.

THANK YOU for words of encouragement re: doctorate and my general work.

After the Mountain: Four Years in the Black Tent

Once winter sets in, the wood-burning stove rarely goes out. In a climate as wet as Britain’s, mold can play havoc with damp canvas, and any tent dweller is constantly sourcing supplies of dry, seasoned wood to see them through the hard months till April. You become accustomed to continually scanning the surrounding hedgerows and copses for any kind of kindling to spark up life-giving heat. To re- turn before dusk with a cord of wood, to light the paraffin lamps, to brew up coffee and warm yourself by the stove are immense pleasures: Wild rabbit in the pot and potatoes in the embers, and reading Cold Mountain poems by the Chinese hermit Han Shan.

Any tent can take awhile to heat, so there’s often a bottle of Lagavulin whisky amongst the axes, billhooks, and rope to sip as the tent creaks into warmth. Weather is to be relished, sworn at, combated, and ultimately worked with. You quickly learn who has the upper hand, and you follow its directives respectfully.

The years in the tent were nomadic; I moved around, but the first location supplied plenty of fallen timber in the surrounding land. What came to my attention, in a field just past the stream, under the barbed wire fence, was a huge oak that had been struck by lightning. Lying on its side, perfectly seasoned by now, it would be, I knew, a very beautiful source of heat for the upcoming winter. Bow saw and rope in hand, I would make my way to the great beast, take what I needed and head back. I could never get too greedy on each trip, as the return journey required too much manoeuvring to carry more than an armful at a time. The wood itself was bleached by weather, almost like driftwood, and burned ferociously. Collecting it was like arriving at the lair of some prehistoric deity with muscled limbs in all directions, and a huge ancient trunk. My time with this tree went through heavy snows, baking summers, and endless British rain. Under a full moon it seemed to glow.

A fire from this source always felt sweeter, more precious. When I fed wood cut to size by the billhook into the hungry mouth of the iron burner, I would sit back and close my eyes, tracing the journey I’d just been on. Words came, mad poems, ornate drawings. After grappling the wood back over the stream and under the fence, some weird excitement would emerge and prowl across the energy of the written word, looking for nests.

Nomadic Voices

Early on I spent a week at a travelers’ camp up on the border between Wales and England. There on the highest field of a well-meaning farmer’s land were a grizzled assortment of Irish travelers, vagabond English, and a small group of traditional Albanian gypsies—a rare mix. The Gypsies, settled for a season or two, were planting the earth, repairing caravans, and traditional wagons, and, apart from berating me to get a haircut, were generally friendly. In the evening they would sit on buckets around an open fire, smoke, and play music, often switching languages as they did it. The stories they told were highly speculative and veered wildly between epic sagas and rough little street tales, packed with intelligence.

What I gained from this experience, in addition to the haircut, was a certain elegance in living outside and a sense of connection to ancestry. It felt precious even then; ten years on I doubt I could even find such a group in England again. As the Gypsies’ music pirouetted defiantly up toward low clouds and old gods, their sons and daughters were focusing their attention on getting an apartment in town or getting a job that paid more than minimum wage. It’s not my business to judge that, because I haven’t lived their life. So I continued wandering and looked for myth tellers, what the Gaelic peoples call the Seanchai—tellers of the deep words. I was lucky enough to meet a few of these people, whether they knew what they were or not.

Their stories were not simple allegories, they were like small bushes of flame. I might hear them up at base camp at Caer Idris, or on a smoke trail from a visiting Mayan, rarely from an “professional storyteller.” I was dazzled, edified and despairing at ever being able to catch some of that nourishing eloquence in my own small beak. I would stagger back to the black tent and watch the word magic bounce around the breathing canvas. Everything that came out of my mouth seemed stumpy, blunt, and factual. It was embarrassing. No wonder my wife had left!

I continued my own journey of listening to the living world. This time it involved being sealed into a small dark structure, like a miniscule sweat lodge, up in the forests of Wales, miles from anyone but my base camper, without food or water. Unable to see my hand in front of my face, or sit up, I was left in the pitch black, clutching three crow feathers and already thirsty. This time the journey was profoundly internal. Deprived of visual light, within a day or so images began to appear across the blackness, like waking dreams. The imagined straight line of time dissolved into something much more profound. The lodge filled with sparks of light and whiskery old voices, the structure itself shook violently. Whole chunks of my future, at that point seemingly unlived, passed by me that night. During the twilight of the second night (not that I could tell), immense storms rolled in from the Irish ocean and set about my tiny structure, assailing it for hours at a time.

When my vigil was done and David, my base camper and long suffering mentor, appeared, I found that trees had come down, the long grasses had flattened, and my tent was awash with water. We made the long and treacherous descent through the forests to David’s car. When we arrived, there was a note from a ranger, worried that the owner had gone out to commit suicide—a popular pastime in that part of Wales. Well, we were both alive in the literal sense, but truly, some part of me had gone up there to die. I remember talking to a Choctaw medicine man about a Lakota friend we had in common, when he said, “Do you

know why he gets so much love? When he walks into the pow wow everyone knows he has died, over and over again.”

As the months moved into years it became clear that the vision-language of tribal people was not just an anthropocentric invention, but arose from a continual openness to the still-latent energies hidden in brook, desert, and moor. I would return from my fasts to the black tent, the old cat, the lightning tree, the witches moon, and wonder.

The Land is a Huge, Dreaming Animal

Places long to speak: great polyphonic blasts of forest oratory or the thin keening of the hemlock. I tried to bathe my head in the golden chatter of holy places, and sometimes caught a word or two, sometimes silence, sometimes a whole stanza of some great epic, buried in the granite of a Dartmoor Tor. The earth’s rough harmonies are more than the metaphors of this writer, but the primordial, root relationship between us and the living world. I have begun to suspect that underneath the ancient caves, buried arrow heads, and mineral deposits, the continents of this world are huge, dreaming animals.

Any gatherings on Ecology may benefit from myth tellers from each country attending and sharing culturally specific stories, so the animals underneath the countries have a chance for the image-language to speak for them. I think these animals have quite different characters and desires.