Tuesday, 24 January 2012

WOOD SISTERS

Winter Storytelling festival on Friday 3rd and Saturday 4th February 2012 at The South Devon Steiner School.

Hey, something great is coming up. A winter storytelling festival, partially a benefit for the WOOD SISTERS - feisty souled storytelling women from down here in the Westcountry. And what a line up: possibly England's most happening poet Alice Oswald, storytelling laureate Katrice Horsley, Chris Salisbury, Tarte Noir, Rebecca Smart, Sarah Hurley, Clive Fairweather, and many other wonderful storytelling, dancing, meditating wonders to be discovered. I am lucky enough to know many of the storytellers on the fliers list (get to see these woman asap) and i say huzzah and right on to the sisters in their enormous effort to construct a red tent for all kinds of spiritual and earthy concerns that i can only guess at. So, a perfect reviver in this dog end of winter. The School of Myth will take a night out from our 'Tasting the Milk of Eagles' weekend to come down on the saturday night where i will be telling the story that helped inspire their good works.

So, in honour and praise of the sisters, some new writing on the sometimes sticky business of the feminine in story - and how far one goes in taking on old ideas of what those phrases masculine and feminine are really about. This is just a tiny segment and so leaves most of that question untouched - it really is just a taster.

The story begins with a king to the east sending a courtier to a women in the west to request a possible marriage....

THE APPLE HEAVY WEST

In many myths there is a woman far to the west, or a woman that lives at the very edge of the world. She is beyond the set up of the sovereigns kingdom, she is an untamed, ecstatic being, but also has a Queenly bearing – her standing outside of the normal boundaries make her appear wild, but her relationship to the mysteries ensures that her crown also carries moon silver and goldenish licks from the Sun Dragon. She is a match. Just the knowledge that a woman like that exists will send the normally staid king utterly crazy with longing.

So the King sends the courtier west. The sovereign within us sets the intention and we, with all our frailties, follow the impulse. The woman is not always about a physical, earthy relationship – much of the emergent 12th century beliefs of courtly love were that they actually needed to stay at a slight distance – it was distance, not erotic fulfilment – that transfigured the attraction up into delirious states of heavenly spirituality. The woman at the edge of the world, what they called ‘the far distant lady’, was a portal to elevated consciousness. A honing of eros into amor.

Equality did not come into it. The woman had to be of a superior rank to the adorer, and so a husband could not cut it. As it was, the marriage already represented an economic and pragmatic situation as so was hardly the ideal setting for the highly charged, adulterous spiritual reckoning that was the longed for pleasure. Certainly in rural France there was still occasional accounts of worship of forest goddesses, and their images lived on in the oral line of storytelling. These ‘far distant ladies’ were not as sexless as the image of Mary, but none the less, served a tricky negotiation between spiritual figure and flesh and blood woman. For many courtly liasons this remained a tense game of poetics and manners, whilst others of course took it a little further, with discreet meetings in hay barns and loving abandon under the willow tree.

A problem for many of us in the notion of ‘the far distant lady’ is passivity; does she sit immobile, valued only for external beauty, whilst all the real adventure is had by the men beating a track to their door? There is a kind of dishing out of roles and expectations that no longer feel appropriate to either women or men. And beauty as the sole source of power? That is a swift route to misery for any women, and just what most main stream media bleats daily. At the same time, is not Elfida’s very receptivity and stillness a vastly needed energy in the world now?

There were of course the Trobaritz, female troubadours scattered over the south. Although there were only a few of them, their poems are earthy, gossipy, imaginative and defiant. Seeing the School of Love through their words paints a rather more dynamic, less celestial scene. Recall Garsenda De Forcalquier;

You’re so well-suited as a lover,

I wish you wouldn’t be so hesitant;

But I’m glad my love makes you the penitent,

Otherwise I’d be the one to suffer.

They seem to watching their backs rather well, and are not the mummified archetypes of male fantasy, but real women enjoying the intrigues and intensities of the role. But still, the role seems confined to those of a youthful and pretty visage.

Whilst a celebration of an aspect of the feminine is be praised over a blanket repression, the feeling none the less remains that maybe that very image itself is inauthentic to a woman’s wider personality. Luckily myth is poly rather than mono, and the search is on for a wider remit of image. It could be dangerous to regard the feminine as ‘other’, just another trick by beardy saboteurs to ostracise and exoticise the experience of being a woman. A woman would have to feel deep into her own nature to get a sense of the truth in that. I know women that seem exhausted, utterly closed to the natural world, rage filled, finger wagging, statistic obsessed - what is the archetype for their disposition? Or the many men in a very similar position, weighed down with a kind of Hercules complex. Of course, both indicate a falling away from psychic health, a disconnect from the renewal that myth and wilderness can offer.

Of course, the language of the sensitive male ‘discovering his feminine side’, is everywhere, and a prime technique for attempting to convincing a woman that you are worthy candidate for sex. Many men are now wonderfully adept at expressing emotion entirely from what they envisage is the ‘feminine side’. This is sometimes a combination of seduction technique and a stunted repression around male emotion that we are all familiar with. If you haven’t witnessed it (mature male feeling), then how do you model it? I recall leading a workshop in Ithaca, New York, with the poet Jay Leeming, as a man claimed that his testicles were really little ‘wombs’. The women present were appalled at this handing over his last remaining shred of maleness, and my own response is not appropriate for the confines of this book.

Who say’s what is an ‘inner-feminine or masculine?’ Is there even a particle of energy left in such a phrase? Why is a man drawing on the feminine if he want to sit quietly in a forest? As a writer you are always looking for where energy crests in language and where it dips, but there appears to be a simple flatline around this. I will occasionally use something approaching that thinking, but I would hope it comes from a sense of life experience not linguistic redundancy.

Rigid clinging to beliefs about men and women’s nature is dangerous, even from the guru Jung himself – a genius with some weak spots in this area. The whole area is far more mutable than it appeared fifty years ago. That said, as a lover of the old stories I suggest that they know things that we do not. They were not all devised in the nineteenth century as devices to imprison and control. Some images, especially troubling ones, are there to convey in image things we may rather not want to look at. To much reliance on myth criticism pushes us to far into analysis and history rather than the lively wisdom’s of the story itself. That we try and constantly interpret the story from the human politics of the history it first arrived in rather than witnessing its changing evolution. So we tread carefully, don’t make too many assumptions but enjoying entertaining possibilities.

To psychologise an experience is to potentially un-lock or see through it, to reduce its hysteria and to give it clarity. To mythologise it is to suggest radiant, un-human energies stand behind that experience as well. The Fates loiter nearby, not just the absent father and difficult childhood. Both are useful at different times. Mythology would suggest that there are certain biological, ontological and supernatural factors within what we call masculine and feminine, as well as possible social instruction, terror of otherness, just plain old patriarchy?

Two thoughts arise at this point:

1. That the call to a deeper life that this woman embodies is becoming a rarer and rarer phenomenon. That many do not travel west, or to the edge of the world, or inwards under a summering oak to mingle with the sensual life she awakens. Sensual does not have to mean sexual. In a world of increased brutality, overwork and ever present distractions, we can be made to believe that the only place for sensuality is in the bedroom. Porn wrecks the emotional infrastructure that is sensitised to an electrical storm, or the flank of a horse, or the pert mounds of an Irish hillside. It wrecks the poet.

So these troubadour links to the sufferings of longing having a religious sensibility tied up with the body of a woman, are a very subtle frequency for most of us these days. So much of the psyche is in exile that we lack the heightened inner-vocabulary to make the journey west.

2. That the image of the woman herself could feel one dimensional, contrived. Where are the hoofed, foul breathed, bad tempered, bloodied thigh dimensions of this character? We know that we don’t have to go far within mythology to meet the terrifying characters of Kali and Yaga, who have no wan young men with lutes serenading them at dusk, rather a bone-pile of clumsy humans surrounding them in steamy piles. The phrase ‘juicy’ that is often used for characters like these is very naïve. Loaded, potent, vast, terrible, maybe better.

The woman at the edge of the world is not really about a human women, and that very lack of roundedness is what makes this a myth, not a novel. Roundedness is what they call ‘characterisation’. It’s what makes certain folks relatable. The myth teller has to walk a line between sensing who within a story holds that roundedness, and who is almost elemental in nature. Elfrida is a radiance, a woman of flowers, some say the soul itself. It would be a good discipline for both men and women reading mythology to not try and cram every scene and character into the human experience. It is a way in – as this book illustrates – but contains many shaded areas that are really for the inhabiting of the invisible world. The stories are not just for us.

I have met many women recently who have simply given up on second hand Jungian archetypes, or inherited notions from books about who or what defines these impulses that move through them. They have chosen a more experiential route. The labour of a craft, relationship to wilderness, handling a business, raising red faced and troubled kids, attention to dreams, delight in making clothes, unconventional lovers, bizarre and un-harmonious opinions, suddenly leaving the idyllic country for a big city.

In other words, they don’t rely on the passivity of received opinion but let the energies that want to speak in their lives arise and be witnessed. The longing for the symbolic world, to reach out towards the curling wave and the lovers call in the nightingale’s song is not a patriarchal trap: it is a call to being a full human being. The key is to find the true resonance of this symbolic world, not just vague platitudes. A life without it can be opening a door to dis-connection, cynicism, even despair.

The emergence of a healthier, more visible, femininity is, unfortunately, a very recent event. I would imagine several decades of feeling our way into an embodied rather than an entirely conceptual sense of feminine and masculine is the right order of things. I know many younger women who are going deeper into their own mysteries, and men also. But their eyes are open: they are neither swallowing wholesale mainstream or cultish dictates about what defines them. They, like the characters in these stories, are on a journey, and will pick up the signs and boons as they go. They may well settle deep into the part of themselves that is indeed in love with distance, ecstasies, the moon – that is indeed a cosmos, indeed connected to the Woman at the Edge of The World, but the thread they hold comes belly deep, from the knowing that comes with the journey.

Copyright Martin Shaw 2012

Winter Storytelling festival on Friday 3rd and Saturday 4th February 2012 at The South Devon Steiner School.

Hey, something great is coming up. A winter storytelling festival, partially a benefit for the WOOD SISTERS - feisty souled storytelling women from down here in the Westcountry. And what a line up: possibly England's most happening poet Alice Oswald, storytelling laureate Katrice Horsley, Chris Salisbury, Tarte Noir, Rebecca Smart, Sarah Hurley, Clive Fairweather, and many other wonderful storytelling, dancing, meditating wonders to be discovered. I am lucky enough to know many of the storytellers on the fliers list (get to see these woman asap) and i say huzzah and right on to the sisters in their enormous effort to construct a red tent for all kinds of spiritual and earthy concerns that i can only guess at. So, a perfect reviver in this dog end of winter. The School of Myth will take a night out from our 'Tasting the Milk of Eagles' weekend to come down on the saturday night where i will be telling the story that helped inspire their good works.

So, in honour and praise of the sisters, some new writing on the sometimes sticky business of the feminine in story - and how far one goes in taking on old ideas of what those phrases masculine and feminine are really about. This is just a tiny segment and so leaves most of that question untouched - it really is just a taster.

The story begins with a king to the east sending a courtier to a women in the west to request a possible marriage....

THE APPLE HEAVY WEST

In many myths there is a woman far to the west, or a woman that lives at the very edge of the world. She is beyond the set up of the sovereigns kingdom, she is an untamed, ecstatic being, but also has a Queenly bearing – her standing outside of the normal boundaries make her appear wild, but her relationship to the mysteries ensures that her crown also carries moon silver and goldenish licks from the Sun Dragon. She is a match. Just the knowledge that a woman like that exists will send the normally staid king utterly crazy with longing.

So the King sends the courtier west. The sovereign within us sets the intention and we, with all our frailties, follow the impulse. The woman is not always about a physical, earthy relationship – much of the emergent 12th century beliefs of courtly love were that they actually needed to stay at a slight distance – it was distance, not erotic fulfilment – that transfigured the attraction up into delirious states of heavenly spirituality. The woman at the edge of the world, what they called ‘the far distant lady’, was a portal to elevated consciousness. A honing of eros into amor.

Equality did not come into it. The woman had to be of a superior rank to the adorer, and so a husband could not cut it. As it was, the marriage already represented an economic and pragmatic situation as so was hardly the ideal setting for the highly charged, adulterous spiritual reckoning that was the longed for pleasure. Certainly in rural France there was still occasional accounts of worship of forest goddesses, and their images lived on in the oral line of storytelling. These ‘far distant ladies’ were not as sexless as the image of Mary, but none the less, served a tricky negotiation between spiritual figure and flesh and blood woman. For many courtly liasons this remained a tense game of poetics and manners, whilst others of course took it a little further, with discreet meetings in hay barns and loving abandon under the willow tree.

A problem for many of us in the notion of ‘the far distant lady’ is passivity; does she sit immobile, valued only for external beauty, whilst all the real adventure is had by the men beating a track to their door? There is a kind of dishing out of roles and expectations that no longer feel appropriate to either women or men. And beauty as the sole source of power? That is a swift route to misery for any women, and just what most main stream media bleats daily. At the same time, is not Elfida’s very receptivity and stillness a vastly needed energy in the world now?

There were of course the Trobaritz, female troubadours scattered over the south. Although there were only a few of them, their poems are earthy, gossipy, imaginative and defiant. Seeing the School of Love through their words paints a rather more dynamic, less celestial scene. Recall Garsenda De Forcalquier;

You’re so well-suited as a lover,

I wish you wouldn’t be so hesitant;

But I’m glad my love makes you the penitent,

Otherwise I’d be the one to suffer.

They seem to watching their backs rather well, and are not the mummified archetypes of male fantasy, but real women enjoying the intrigues and intensities of the role. But still, the role seems confined to those of a youthful and pretty visage.

Whilst a celebration of an aspect of the feminine is be praised over a blanket repression, the feeling none the less remains that maybe that very image itself is inauthentic to a woman’s wider personality. Luckily myth is poly rather than mono, and the search is on for a wider remit of image. It could be dangerous to regard the feminine as ‘other’, just another trick by beardy saboteurs to ostracise and exoticise the experience of being a woman. A woman would have to feel deep into her own nature to get a sense of the truth in that. I know women that seem exhausted, utterly closed to the natural world, rage filled, finger wagging, statistic obsessed - what is the archetype for their disposition? Or the many men in a very similar position, weighed down with a kind of Hercules complex. Of course, both indicate a falling away from psychic health, a disconnect from the renewal that myth and wilderness can offer.

Of course, the language of the sensitive male ‘discovering his feminine side’, is everywhere, and a prime technique for attempting to convincing a woman that you are worthy candidate for sex. Many men are now wonderfully adept at expressing emotion entirely from what they envisage is the ‘feminine side’. This is sometimes a combination of seduction technique and a stunted repression around male emotion that we are all familiar with. If you haven’t witnessed it (mature male feeling), then how do you model it? I recall leading a workshop in Ithaca, New York, with the poet Jay Leeming, as a man claimed that his testicles were really little ‘wombs’. The women present were appalled at this handing over his last remaining shred of maleness, and my own response is not appropriate for the confines of this book.

Who say’s what is an ‘inner-feminine or masculine?’ Is there even a particle of energy left in such a phrase? Why is a man drawing on the feminine if he want to sit quietly in a forest? As a writer you are always looking for where energy crests in language and where it dips, but there appears to be a simple flatline around this. I will occasionally use something approaching that thinking, but I would hope it comes from a sense of life experience not linguistic redundancy.

Rigid clinging to beliefs about men and women’s nature is dangerous, even from the guru Jung himself – a genius with some weak spots in this area. The whole area is far more mutable than it appeared fifty years ago. That said, as a lover of the old stories I suggest that they know things that we do not. They were not all devised in the nineteenth century as devices to imprison and control. Some images, especially troubling ones, are there to convey in image things we may rather not want to look at. To much reliance on myth criticism pushes us to far into analysis and history rather than the lively wisdom’s of the story itself. That we try and constantly interpret the story from the human politics of the history it first arrived in rather than witnessing its changing evolution. So we tread carefully, don’t make too many assumptions but enjoying entertaining possibilities.

To psychologise an experience is to potentially un-lock or see through it, to reduce its hysteria and to give it clarity. To mythologise it is to suggest radiant, un-human energies stand behind that experience as well. The Fates loiter nearby, not just the absent father and difficult childhood. Both are useful at different times. Mythology would suggest that there are certain biological, ontological and supernatural factors within what we call masculine and feminine, as well as possible social instruction, terror of otherness, just plain old patriarchy?

Two thoughts arise at this point:

1. That the call to a deeper life that this woman embodies is becoming a rarer and rarer phenomenon. That many do not travel west, or to the edge of the world, or inwards under a summering oak to mingle with the sensual life she awakens. Sensual does not have to mean sexual. In a world of increased brutality, overwork and ever present distractions, we can be made to believe that the only place for sensuality is in the bedroom. Porn wrecks the emotional infrastructure that is sensitised to an electrical storm, or the flank of a horse, or the pert mounds of an Irish hillside. It wrecks the poet.

So these troubadour links to the sufferings of longing having a religious sensibility tied up with the body of a woman, are a very subtle frequency for most of us these days. So much of the psyche is in exile that we lack the heightened inner-vocabulary to make the journey west.

2. That the image of the woman herself could feel one dimensional, contrived. Where are the hoofed, foul breathed, bad tempered, bloodied thigh dimensions of this character? We know that we don’t have to go far within mythology to meet the terrifying characters of Kali and Yaga, who have no wan young men with lutes serenading them at dusk, rather a bone-pile of clumsy humans surrounding them in steamy piles. The phrase ‘juicy’ that is often used for characters like these is very naïve. Loaded, potent, vast, terrible, maybe better.

The woman at the edge of the world is not really about a human women, and that very lack of roundedness is what makes this a myth, not a novel. Roundedness is what they call ‘characterisation’. It’s what makes certain folks relatable. The myth teller has to walk a line between sensing who within a story holds that roundedness, and who is almost elemental in nature. Elfrida is a radiance, a woman of flowers, some say the soul itself. It would be a good discipline for both men and women reading mythology to not try and cram every scene and character into the human experience. It is a way in – as this book illustrates – but contains many shaded areas that are really for the inhabiting of the invisible world. The stories are not just for us.

I have met many women recently who have simply given up on second hand Jungian archetypes, or inherited notions from books about who or what defines these impulses that move through them. They have chosen a more experiential route. The labour of a craft, relationship to wilderness, handling a business, raising red faced and troubled kids, attention to dreams, delight in making clothes, unconventional lovers, bizarre and un-harmonious opinions, suddenly leaving the idyllic country for a big city.

In other words, they don’t rely on the passivity of received opinion but let the energies that want to speak in their lives arise and be witnessed. The longing for the symbolic world, to reach out towards the curling wave and the lovers call in the nightingale’s song is not a patriarchal trap: it is a call to being a full human being. The key is to find the true resonance of this symbolic world, not just vague platitudes. A life without it can be opening a door to dis-connection, cynicism, even despair.

The emergence of a healthier, more visible, femininity is, unfortunately, a very recent event. I would imagine several decades of feeling our way into an embodied rather than an entirely conceptual sense of feminine and masculine is the right order of things. I know many younger women who are going deeper into their own mysteries, and men also. But their eyes are open: they are neither swallowing wholesale mainstream or cultish dictates about what defines them. They, like the characters in these stories, are on a journey, and will pick up the signs and boons as they go. They may well settle deep into the part of themselves that is indeed in love with distance, ecstasies, the moon – that is indeed a cosmos, indeed connected to the Woman at the Edge of The World, but the thread they hold comes belly deep, from the knowing that comes with the journey.

Copyright Martin Shaw 2012

Thursday, 19 January 2012

something fresh out of the pot this week - from a new book i'm working on - some chunks of story related themes that may prove interesting. Great time in London at Tongue Fu last week, so packed i had to go up three flights of stairs just to get a chair from which to tell my story from (needed seat for frame drum). A great bunch, and a lovely time in the east end - i'll drop some lines about it here soon - it sneaked into this new book.

What is Mythtelling?

I use the word mythtelling rather than storytelling sometimes to indicate that these stories (in book) are more than just folklore – more than the intelligence of the village figuring their place out in the world. Mythtelling has a wider context, that the stories may come from a ridge of mountain, cloud or deity. It’s not meant as a form of pretension, but to highlight this less anthropocentric emphasis.

The first road maps of the British isles used to include detailed sketches and information about forests, lakes, rivers and mountains. They were not just negligible blurs between service stations. I would hope that mythtelling restates that attention within story. That we are not just caught up in the twin-lane highway drama of the human characters, but keep an eye for the lucid twinkles of ravens eye, or the bright sap on the crust of a rowan trees bark. To mention it constantly would make it self-conscious, but it will come up occasionally as a gentle re-orientation.

I have had a long standing involvement with wilderness rites-of-passage work. It involves a protracted fast in a wilderness area with an ear to the visionary – a very old practice on Dartmoor and all over the world. It means my relationship with myth is very specific, rather narrow some could call it. It’s a sympathy with what I call prophetic stories rather than pastoral. Stories that seem to have wet black roots, rather than squeezed entirely into a human anecdote. There are many different definitions of myth - quite opposed to mine, and can be sought out easily.

The Protean Era

With the revival of the storytelling tradition, and a simultaneous focus on the bio-regional, it seems appropriate to recognise that local folklore can be just as nourishing as a plate of fresh vegetables from the garden or a haunch of venison from a nearby forest. It is a form of soul food. This book is about that very thing. Just as the farmers market is growing happily against the onslaught of the supermarket, and allotments have waiting lists for the first time in a generation, I am suggesting that the vitality of localised myth can be just as crucial to the health of our own inner-ecosystem. In this next section I will move between both the gains involved in this immediate knowledge, and acknowledging the wider pantheon of story that is now readily available. It may be a frustration that I will not promote one entirely over the other, but I hope as we go my thoughts will become clear.

Story orientates: and not just to the immediate, geographical landscape but to wider, eternal concerns: concerns of the soul. It’s for this reason we sense the resonance of a Russian epic right down in the gut, we laugh out loud at the bawdy intelligence of a wolverine tale from Labrador, despite having been raised in an different time and space. I would call that nomadic recognition – past the cultural flavours and directly to the energy that lives behind it. It’s the power of truly vital image; we are shot clean of everyday reference and abide in its almost electrical refreshment, that, for a moment, hangs above specific fields of cultural association. However, for most there has not always been such a wide field of reference. Many human groups throughout history, have, for the most part, enjoyed a geographically specific relationship to the stories they tell. Of course a certain amount of cultural diffusion can be present, but is often waywardly pulled into the local over time. This generation spanning, steady telling I would call slow ground. It’s a localised cosmos that roots you steady in it. It confirms you, your thinking, your rituals and your tribe, establishes place, and reveals with a slow drip drip drip, the mythic energies you stand upon.

This slow ground is becoming rapidly fragmented in what many call a Protean age. Proteus is a shape-shifting god of the sea – mutable, able to swiftly change position. With the ludicrously intense barrage of information that we daily face, a kind of mimic of the nomadic leap becomes far more common parley than this slow ground. We multi-task to the last, digesting intestinal-wrecking amounts of stress in the bargain. The TV show, jerkily cutting from camera to camera, illustrates this malaise in a way we all understand. It seems to be revealing some great restlessness of spirit, way down inside.

The Commons of the Imagination

A major factor of nomadic recognition within storytelling – this experience of possibly unknown but somehow emotionally recognised image - is then the move back to slow ground to root it in the discipline of crafting and telling the story. The performative. It re-finds its ground by the labour of telling – it grows roots. It cannot entirely replace the origination point of the story, but stories are living beings, origination points are a birthing but not an ending of it. Slowly the story becomes settled visually in the inner-landscape of the teller and the listeners. That inner-landscape will not be the same for everyone. Although the experience can be very deep, we are seeing different locations, geographies, visual triggers. The image-net is wider. James Hillman talks about “the return to Greece” not as a physical journey to the Mediterranean but as a revival of pantheistic consciousness. That is the trade for learning of these stories. They enter a cross-culture commons of the imagination. They abide not in a particular gully or narrow mountain range (except for a very few listeners) but have ended up in the wide, rainbow’ed vista of collective information. From this commons many apprentice storytellers wander excitedly through, gathering a bulb of Hungarian folklore here, a herb or two from Tibet over there.

Of course, this all seems like a snapshot of so much that is wrong with modern life. That the specific and vital becomes the generic and jumbled. As Tom Waits say’s “ a song needs an address”. We en-soul something by naming it, a detail anchors it in more than a floating intelligence. By taking the original localised references out of the story have we somehow robbed it of its soul? Yes and no - I cannot go along with that entirely. I would suggest that what is needed within this collective information is a greater connection to one’s own roots. I would do away with the rainbowed, new age picture of everything as one, and more the image of a sea port, or desert meeting place, or crossroads inn, where cultures and travellers swap stories, recipe’s, opinions, songs - and all leave deepened by the exchange but also confirmed in their own ground.

My concern within myth is that the collective commons is overwhelming the local – we end up with storyteller’s floating several feet above their own ground, constantly enthralled with the exotic, wider picture.

Of course, some stories travel but also have a specificity that locks it into a particular location. In 1284, a man with a brightly coloured coat arrived at the edge of the town of Hamelin. He had an unusual ability; he claimed his pipe could lure all the rats and mice out of the area. For a sum of coin. They agreed and the ‘Brightman’ started to play. From every guttering, shed, woodstore, house and privy came the rats. When all were gathered he turned and walked towards the Weser river, still playing. He then took of his clothes and entered the water. The rats, still entranced, followed him and drowned. Despite the clear success of his venture, the locals reneged on the deal and would not pay. On the 26th June he returned, this time dressed as a hunter with a strange red hat, and started to play again. This time it was not rats but children that followed him, even the mayors daughter. As a flock he led them to a nearby mountain where he and the children were never seen again. Maybe it was the early hour – 7am – but none but a nanny saw them leave, and she alerted the wider community. Despite desperate searching none could be found. A boy that has run back to his gather his jacket was able to lead the adults to a hole in the side of the hill and claimed they had gone inside. The event was documented in town records, and inscribed on the town hall these words:

In the year 1284 A.D.

130 children born in Hamelin

were led out of our town

by a piper and lost in the mountain

Although speculation persists that they were taken for a children’s crusade, or a better economic life somewhere else, or that it is a cover up for a plague that took their lives, all we know is that it was an event that was noted in the records of the day as an actual event, in a specific place. The street the children took to leave the town is still called the Street of Silence, and no music is allowed to be played there. What is fascinating is that the detail of rats do not get mentioned until 1556 by the theologian Jobus Fincelius – rat catchers being very much a character of the era, and possibly a storyteller’s addition. What we can say is that something deeply traumatic happened to the people of Hamelin around the year 1284.

So the grief of the event, and its anchoring within time and space, grounds it still in a particular location. This event in particular alerts us to perennial fears of the brooding wilderness that lurks beyond the ploughed field, and also of ‘Brightmen’ who carry the medicine of animals and music, who abide the other side of the village gates. But many other stories travel and gradually lose the specifics, the place names – or a nimble teller will just swiftly change them to something more local.

Anthropologist’s correctly point out that we miss much local nuance in this wider embracing. How do we grasp the role of the duck in a Seneca love story? Or approach any real knowledge of ritual colours in a Dagara folk tale? Only through a possibly dry academic approach can we get near an appraisal. Well true enough, on one level. If the story is entirely conceptually bound to that tribe or place. But what if it also has a travelling spirit? A sprit that is bound up in the telling of the story, there in the room, more than being entirely anchored in a historical context. That it is a kind of animal.

There is damage in all of this it’s clear. It’s a complex situation, but I believe caution is needed when myth is described as only rooted in history, culture and geography. Myth on a deep level really isn’t all about history, rather a truly animistic present. But we also may relate to a sense of numbness when presented with yet another anthropological marvel of folk tales from some far off place. The sheer velocity of availability dulls the mind. Sometimes, as the poet Olav Hauge reminds us, we just need a sip of water, not the whole ocean.

In all of this scope - of firebird feathers, and Tuvan blades, of African genies and the hooves of Mongolian steeds riding briskly through a star-lit desert - it can be easy to get a little dismissive of the local. Surely nothing of note happened right here? And sometimes that can seem to be the case. We look around at inner-cites, or remote stretches of Lincolnshire fields and think the old stories, if there ever where any, have long fled. But nowhere is bereft of story, if we have some patience and an enquiring spirit. This book is about finding some slow ground for those nomadic leaps to land upon.

I sometimes think of the old East Anglian tale of “The Peddler of Swaffham”: a story of a man’s long journey across half the country because of a dream of fortune, only to find that that the very dream-gold is buried in his back yard. Journeys are good, voyages better, but I write this in the hope we do not neglect the gold that is in on our very doorstep.

Copyright Martin Shaw 2012

What is Mythtelling?

I use the word mythtelling rather than storytelling sometimes to indicate that these stories (in book) are more than just folklore – more than the intelligence of the village figuring their place out in the world. Mythtelling has a wider context, that the stories may come from a ridge of mountain, cloud or deity. It’s not meant as a form of pretension, but to highlight this less anthropocentric emphasis.

The first road maps of the British isles used to include detailed sketches and information about forests, lakes, rivers and mountains. They were not just negligible blurs between service stations. I would hope that mythtelling restates that attention within story. That we are not just caught up in the twin-lane highway drama of the human characters, but keep an eye for the lucid twinkles of ravens eye, or the bright sap on the crust of a rowan trees bark. To mention it constantly would make it self-conscious, but it will come up occasionally as a gentle re-orientation.

I have had a long standing involvement with wilderness rites-of-passage work. It involves a protracted fast in a wilderness area with an ear to the visionary – a very old practice on Dartmoor and all over the world. It means my relationship with myth is very specific, rather narrow some could call it. It’s a sympathy with what I call prophetic stories rather than pastoral. Stories that seem to have wet black roots, rather than squeezed entirely into a human anecdote. There are many different definitions of myth - quite opposed to mine, and can be sought out easily.

The Protean Era

With the revival of the storytelling tradition, and a simultaneous focus on the bio-regional, it seems appropriate to recognise that local folklore can be just as nourishing as a plate of fresh vegetables from the garden or a haunch of venison from a nearby forest. It is a form of soul food. This book is about that very thing. Just as the farmers market is growing happily against the onslaught of the supermarket, and allotments have waiting lists for the first time in a generation, I am suggesting that the vitality of localised myth can be just as crucial to the health of our own inner-ecosystem. In this next section I will move between both the gains involved in this immediate knowledge, and acknowledging the wider pantheon of story that is now readily available. It may be a frustration that I will not promote one entirely over the other, but I hope as we go my thoughts will become clear.

Story orientates: and not just to the immediate, geographical landscape but to wider, eternal concerns: concerns of the soul. It’s for this reason we sense the resonance of a Russian epic right down in the gut, we laugh out loud at the bawdy intelligence of a wolverine tale from Labrador, despite having been raised in an different time and space. I would call that nomadic recognition – past the cultural flavours and directly to the energy that lives behind it. It’s the power of truly vital image; we are shot clean of everyday reference and abide in its almost electrical refreshment, that, for a moment, hangs above specific fields of cultural association. However, for most there has not always been such a wide field of reference. Many human groups throughout history, have, for the most part, enjoyed a geographically specific relationship to the stories they tell. Of course a certain amount of cultural diffusion can be present, but is often waywardly pulled into the local over time. This generation spanning, steady telling I would call slow ground. It’s a localised cosmos that roots you steady in it. It confirms you, your thinking, your rituals and your tribe, establishes place, and reveals with a slow drip drip drip, the mythic energies you stand upon.

This slow ground is becoming rapidly fragmented in what many call a Protean age. Proteus is a shape-shifting god of the sea – mutable, able to swiftly change position. With the ludicrously intense barrage of information that we daily face, a kind of mimic of the nomadic leap becomes far more common parley than this slow ground. We multi-task to the last, digesting intestinal-wrecking amounts of stress in the bargain. The TV show, jerkily cutting from camera to camera, illustrates this malaise in a way we all understand. It seems to be revealing some great restlessness of spirit, way down inside.

The Commons of the Imagination

A major factor of nomadic recognition within storytelling – this experience of possibly unknown but somehow emotionally recognised image - is then the move back to slow ground to root it in the discipline of crafting and telling the story. The performative. It re-finds its ground by the labour of telling – it grows roots. It cannot entirely replace the origination point of the story, but stories are living beings, origination points are a birthing but not an ending of it. Slowly the story becomes settled visually in the inner-landscape of the teller and the listeners. That inner-landscape will not be the same for everyone. Although the experience can be very deep, we are seeing different locations, geographies, visual triggers. The image-net is wider. James Hillman talks about “the return to Greece” not as a physical journey to the Mediterranean but as a revival of pantheistic consciousness. That is the trade for learning of these stories. They enter a cross-culture commons of the imagination. They abide not in a particular gully or narrow mountain range (except for a very few listeners) but have ended up in the wide, rainbow’ed vista of collective information. From this commons many apprentice storytellers wander excitedly through, gathering a bulb of Hungarian folklore here, a herb or two from Tibet over there.

Of course, this all seems like a snapshot of so much that is wrong with modern life. That the specific and vital becomes the generic and jumbled. As Tom Waits say’s “ a song needs an address”. We en-soul something by naming it, a detail anchors it in more than a floating intelligence. By taking the original localised references out of the story have we somehow robbed it of its soul? Yes and no - I cannot go along with that entirely. I would suggest that what is needed within this collective information is a greater connection to one’s own roots. I would do away with the rainbowed, new age picture of everything as one, and more the image of a sea port, or desert meeting place, or crossroads inn, where cultures and travellers swap stories, recipe’s, opinions, songs - and all leave deepened by the exchange but also confirmed in their own ground.

My concern within myth is that the collective commons is overwhelming the local – we end up with storyteller’s floating several feet above their own ground, constantly enthralled with the exotic, wider picture.

Of course, some stories travel but also have a specificity that locks it into a particular location. In 1284, a man with a brightly coloured coat arrived at the edge of the town of Hamelin. He had an unusual ability; he claimed his pipe could lure all the rats and mice out of the area. For a sum of coin. They agreed and the ‘Brightman’ started to play. From every guttering, shed, woodstore, house and privy came the rats. When all were gathered he turned and walked towards the Weser river, still playing. He then took of his clothes and entered the water. The rats, still entranced, followed him and drowned. Despite the clear success of his venture, the locals reneged on the deal and would not pay. On the 26th June he returned, this time dressed as a hunter with a strange red hat, and started to play again. This time it was not rats but children that followed him, even the mayors daughter. As a flock he led them to a nearby mountain where he and the children were never seen again. Maybe it was the early hour – 7am – but none but a nanny saw them leave, and she alerted the wider community. Despite desperate searching none could be found. A boy that has run back to his gather his jacket was able to lead the adults to a hole in the side of the hill and claimed they had gone inside. The event was documented in town records, and inscribed on the town hall these words:

In the year 1284 A.D.

130 children born in Hamelin

were led out of our town

by a piper and lost in the mountain

Although speculation persists that they were taken for a children’s crusade, or a better economic life somewhere else, or that it is a cover up for a plague that took their lives, all we know is that it was an event that was noted in the records of the day as an actual event, in a specific place. The street the children took to leave the town is still called the Street of Silence, and no music is allowed to be played there. What is fascinating is that the detail of rats do not get mentioned until 1556 by the theologian Jobus Fincelius – rat catchers being very much a character of the era, and possibly a storyteller’s addition. What we can say is that something deeply traumatic happened to the people of Hamelin around the year 1284.

So the grief of the event, and its anchoring within time and space, grounds it still in a particular location. This event in particular alerts us to perennial fears of the brooding wilderness that lurks beyond the ploughed field, and also of ‘Brightmen’ who carry the medicine of animals and music, who abide the other side of the village gates. But many other stories travel and gradually lose the specifics, the place names – or a nimble teller will just swiftly change them to something more local.

Anthropologist’s correctly point out that we miss much local nuance in this wider embracing. How do we grasp the role of the duck in a Seneca love story? Or approach any real knowledge of ritual colours in a Dagara folk tale? Only through a possibly dry academic approach can we get near an appraisal. Well true enough, on one level. If the story is entirely conceptually bound to that tribe or place. But what if it also has a travelling spirit? A sprit that is bound up in the telling of the story, there in the room, more than being entirely anchored in a historical context. That it is a kind of animal.

There is damage in all of this it’s clear. It’s a complex situation, but I believe caution is needed when myth is described as only rooted in history, culture and geography. Myth on a deep level really isn’t all about history, rather a truly animistic present. But we also may relate to a sense of numbness when presented with yet another anthropological marvel of folk tales from some far off place. The sheer velocity of availability dulls the mind. Sometimes, as the poet Olav Hauge reminds us, we just need a sip of water, not the whole ocean.

In all of this scope - of firebird feathers, and Tuvan blades, of African genies and the hooves of Mongolian steeds riding briskly through a star-lit desert - it can be easy to get a little dismissive of the local. Surely nothing of note happened right here? And sometimes that can seem to be the case. We look around at inner-cites, or remote stretches of Lincolnshire fields and think the old stories, if there ever where any, have long fled. But nowhere is bereft of story, if we have some patience and an enquiring spirit. This book is about finding some slow ground for those nomadic leaps to land upon.

I sometimes think of the old East Anglian tale of “The Peddler of Swaffham”: a story of a man’s long journey across half the country because of a dream of fortune, only to find that that the very dream-gold is buried in his back yard. Journeys are good, voyages better, but I write this in the hope we do not neglect the gold that is in on our very doorstep.

Copyright Martin Shaw 2012

Wednesday, 11 January 2012

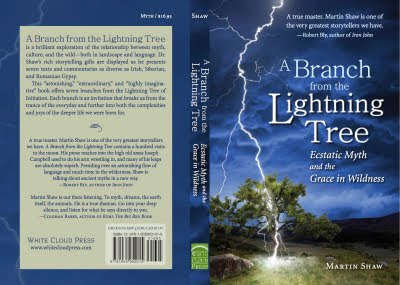

Something i am sure i posted some time back this week, but a little refresher can be useful. It's from Lightning Tree and looks at some of Jaques Derrida's ideas and how they relate to modern day storytelling and actually the notion of initiation itself. I value the ideas and how it rubs up against the near impossibility of claiming a purely oral tradition in the west when our speech is now already so influenced by writing - and how that rub is actually very creative, very interesting.

I'm in London tomorrow night - at TONGUE FU, at rich mix, 35-47 Bethnal Green rd, 7.30 to 11pm. Telling a big story, Come down and find out what it is! Alongside some the wonderful Malika Booker and Tim Claire. These are high end evenings in terms of quality performers, so do keep checking out their events. Ok, better start packing. Johnny Bloor turns up at first light for the long drive - a day in Foyles bookshop on the Charing Cross road sipping frappabrandychino's in the esoteric section i think, then onto the misty east end. Hope to see you there!

Trickster Language

I want to deepen this idea of a crossroads, by how it relates both to initiatory practice and the relationship between speech and literature. It would be useful to get a sense of where the ideas in this book place themselves, situated both in oral myth-telling and the page. The philosopher Jaques Derrida maintained that for over 3,000 years of Western philosophy, philosophers have claimed logocentrism–that the voice is the center, from Plato to Aristotle, to Rosseau, Hegel and Husseri. So languages are made to be spoken. Writing serves only as a support to speech. This idea would regard speech as exterior to thought, and writing as exterior to speech. There is a clear and distinct sense of hierarchy—a regression from mind to voice to letter.

From the perspective of logocentrism, presence is implicit in the communication of speech, but for writing, absence is the defining characteristic. So with speech, the listener and speaker are both present in time, and present to the succession of words from the mouth. The image of letters on a page, wrapped in an envelope, and sent to a distant figure, illustrates the concept of absence.

So writing becomes marginalized, quite opposed to Derrida’s notion that the development of modern language actually derives from an interplay of speech and writing, therefore one cannot claim primacy over the other.

Like keen-eye Trickster, Derrida also disrupts this old oppositional thinking by locating what he calls “undecidables.” Specifically concepts or words that cannot be brought into a binary logic. They unsettle. A phrase like Pharmakon, which means both poison and remedy. An “undecidable” within the context of a wilderness rite- of-passage would be contact with a spirit—rarely conforming to a hegemonic form—something neither male or female, a disruption to normality. Indeterminacy–it indicates no precision, clarity, or easy definition. Initiatory process indicates that it is only in the surrender to this difficult awareness that any real vision can ultimately arise (hence the severing from certainty that takes place). Initiation places you in the slippery crucible of paradox. With time this evolves, and insights emerge, but not without the profound drop into this contrary Underworld. You are neither Village or Forest, but some other, subtle thing. The world turned upside down. It’s a hard thing to talk about.

This book’s position is one of intense interplay, a shuttling between. Speech is occurring within the writing and writing is

occurring within the speech. Many insights have come from telling a story orally, which is in turn influenced by years at the desk. What arrives seems to have a liminal touch, a betwixt and between. For the book to work within what Derrida—and Heidegger before him—refers to as “the metaphysics of presence” (the old position), the crossroads motif cannot exist, no matter how nebulous. Inter- estingly, the logocentric is a position many oral storytellers would support, being central to their craft. I disagree. Where I do speak up is in the call for the spontaneous within an oral telling, the wild Intelligence that arrives in the moment—but that does not belittle writing or its influence, just a script used inappropriately.

Like Trickster, Derrida is not interested in eradicating what came before, but in helping to engender some new constellation. He also draws from the past—writing about literary texts— while using such a contrary linguistic style it appears that the sentences are breaking down and reconfiguring in front of your eyes.

By working with host texts, Derrida actually requires the oppositions of past literature to find the instabilities that open the ground of uncertainty. Think again of Trickster: “The god of the roads (trickster) needs the more settled territories before his traveling means very much. If everyone travels, the result is not the apotheosis of trickster but another form of his demise,” explains Lewis Hyde.19 This is an ancient ritual arrangement, the trammelling of boundaries to ensure that vitality tickles the status quo and life continues to grow. Trickster is nothing without something to rub up against.

As Derrida shakes the foundations of both structuralism and phenomenology, there is a loyalty to some wild spirit of

investigation that is both troubling and refreshing. As an old oak collapses, at the same moment a green shoot leaps from the earth. Speech and writing always hold the energies of history, influence, and repetition among them. Derrida is in the business of hints and diffusion, traditional attributes of the Underworld journey, rather than brightly lit sound bites. Still, when the young initiates are led from the village, they are blindfolded, spun round, turned up side down–they are now in submission to a fiercer dynamic. This is all in the nature of rupture. Derrida is being true to his work.

Copyright White Cloud Press 2011

I'm in London tomorrow night - at TONGUE FU, at rich mix, 35-47 Bethnal Green rd, 7.30 to 11pm. Telling a big story, Come down and find out what it is! Alongside some the wonderful Malika Booker and Tim Claire. These are high end evenings in terms of quality performers, so do keep checking out their events. Ok, better start packing. Johnny Bloor turns up at first light for the long drive - a day in Foyles bookshop on the Charing Cross road sipping frappabrandychino's in the esoteric section i think, then onto the misty east end. Hope to see you there!

Trickster Language

I want to deepen this idea of a crossroads, by how it relates both to initiatory practice and the relationship between speech and literature. It would be useful to get a sense of where the ideas in this book place themselves, situated both in oral myth-telling and the page. The philosopher Jaques Derrida maintained that for over 3,000 years of Western philosophy, philosophers have claimed logocentrism–that the voice is the center, from Plato to Aristotle, to Rosseau, Hegel and Husseri. So languages are made to be spoken. Writing serves only as a support to speech. This idea would regard speech as exterior to thought, and writing as exterior to speech. There is a clear and distinct sense of hierarchy—a regression from mind to voice to letter.

From the perspective of logocentrism, presence is implicit in the communication of speech, but for writing, absence is the defining characteristic. So with speech, the listener and speaker are both present in time, and present to the succession of words from the mouth. The image of letters on a page, wrapped in an envelope, and sent to a distant figure, illustrates the concept of absence.

So writing becomes marginalized, quite opposed to Derrida’s notion that the development of modern language actually derives from an interplay of speech and writing, therefore one cannot claim primacy over the other.

Like keen-eye Trickster, Derrida also disrupts this old oppositional thinking by locating what he calls “undecidables.” Specifically concepts or words that cannot be brought into a binary logic. They unsettle. A phrase like Pharmakon, which means both poison and remedy. An “undecidable” within the context of a wilderness rite- of-passage would be contact with a spirit—rarely conforming to a hegemonic form—something neither male or female, a disruption to normality. Indeterminacy–it indicates no precision, clarity, or easy definition. Initiatory process indicates that it is only in the surrender to this difficult awareness that any real vision can ultimately arise (hence the severing from certainty that takes place). Initiation places you in the slippery crucible of paradox. With time this evolves, and insights emerge, but not without the profound drop into this contrary Underworld. You are neither Village or Forest, but some other, subtle thing. The world turned upside down. It’s a hard thing to talk about.

This book’s position is one of intense interplay, a shuttling between. Speech is occurring within the writing and writing is

occurring within the speech. Many insights have come from telling a story orally, which is in turn influenced by years at the desk. What arrives seems to have a liminal touch, a betwixt and between. For the book to work within what Derrida—and Heidegger before him—refers to as “the metaphysics of presence” (the old position), the crossroads motif cannot exist, no matter how nebulous. Inter- estingly, the logocentric is a position many oral storytellers would support, being central to their craft. I disagree. Where I do speak up is in the call for the spontaneous within an oral telling, the wild Intelligence that arrives in the moment—but that does not belittle writing or its influence, just a script used inappropriately.

Like Trickster, Derrida is not interested in eradicating what came before, but in helping to engender some new constellation. He also draws from the past—writing about literary texts— while using such a contrary linguistic style it appears that the sentences are breaking down and reconfiguring in front of your eyes.

By working with host texts, Derrida actually requires the oppositions of past literature to find the instabilities that open the ground of uncertainty. Think again of Trickster: “The god of the roads (trickster) needs the more settled territories before his traveling means very much. If everyone travels, the result is not the apotheosis of trickster but another form of his demise,” explains Lewis Hyde.19 This is an ancient ritual arrangement, the trammelling of boundaries to ensure that vitality tickles the status quo and life continues to grow. Trickster is nothing without something to rub up against.

As Derrida shakes the foundations of both structuralism and phenomenology, there is a loyalty to some wild spirit of

investigation that is both troubling and refreshing. As an old oak collapses, at the same moment a green shoot leaps from the earth. Speech and writing always hold the energies of history, influence, and repetition among them. Derrida is in the business of hints and diffusion, traditional attributes of the Underworld journey, rather than brightly lit sound bites. Still, when the young initiates are led from the village, they are blindfolded, spun round, turned up side down–they are now in submission to a fiercer dynamic. This is all in the nature of rupture. Derrida is being true to his work.

Copyright White Cloud Press 2011

Thursday, 5 January 2012

TASTING THE MILK OF EAGLES: A New Weekend at the School of Myth

Just posting this - new ideas, new stories, new challenges for 2012. Please 'share' and spread the word, that would be much appreciated. I am very much looking forward to this! Cheers, Martin.

Friday, February 3, 2012 at 8:00pm until Sunday, February 5, 2012 at 4:00pm

Where: Blytheswood Hostel, Steps Bridge, Dunsford, Exeter, Devon EX6 7EQ

A WEEKEND GATHERING SPECIFICALLY CONCERNING MYTH AND INITIATION with storyteller and mythologist Dr. Martin Shaw. This weekend (the 3rd in the ongoing year programme, but all are welcome), features initiation stories from the tribal edge: the Nart Sagas of the Caucacus mountains, the Seneca Indians of the forests of the east coast of America and an ancient Polish fairy tale. Much of the material and ideas explored are brand new to the School of Myth programme.

All of the stories are to do with the edges, scuffs and challenges that we face as we grow older. How do we indeed 'taste the milk of eagles', rather than move into the disappointment and numbness we see in society at large? In a time of rioting in the capital and chronic dis-connect could there be information for us in the old tales? The content of these stories are both very sophisticated and deeply moving. They have implications we are only just beginning to explore in the west.

Throughout the weekend we will delve very deep into the stories relevance to our own lives, learn more about the motivation behind the ancient initiation practices found around the world and learn a variety of powerful exercises to help forge a relationship to the living world. Shaw will also be using the weekend specifically to layout what he calls 'foundational stones to mythtelling' - unmissable for any apprentice storytellers.

On the Saturday night an unexpected treat: we will be visiting the Wood Sisters Winter Storytelling festival in nearby Dartington where Martin will perform 'The Handless Maiden', and we will also witness the new storytelling Laureate of Great Britain, Katrice Horsley. Do not miss this juiciest of weekends - fellowship, laughter, stories shared, great food and wild possibility!

EMAIL tina. schoolofmyth@yahoo.com TODAY for place.

01364 653723 for more details

170 pounds (50 pounds non-refundable deposit), fully residential. More details on contact with Tina Birchill.

www.schoolofmyth.com

Friday, February 3, 2012 at 8:00pm until Sunday, February 5, 2012 at 4:00pm

Where: Blytheswood Hostel, Steps Bridge, Dunsford, Exeter, Devon EX6 7EQ

A WEEKEND GATHERING SPECIFICALLY CONCERNING MYTH AND INITIATION with storyteller and mythologist Dr. Martin Shaw. This weekend (the 3rd in the ongoing year programme, but all are welcome), features initiation stories from the tribal edge: the Nart Sagas of the Caucacus mountains, the Seneca Indians of the forests of the east coast of America and an ancient Polish fairy tale. Much of the material and ideas explored are brand new to the School of Myth programme.

All of the stories are to do with the edges, scuffs and challenges that we face as we grow older. How do we indeed 'taste the milk of eagles', rather than move into the disappointment and numbness we see in society at large? In a time of rioting in the capital and chronic dis-connect could there be information for us in the old tales? The content of these stories are both very sophisticated and deeply moving. They have implications we are only just beginning to explore in the west.

Throughout the weekend we will delve very deep into the stories relevance to our own lives, learn more about the motivation behind the ancient initiation practices found around the world and learn a variety of powerful exercises to help forge a relationship to the living world. Shaw will also be using the weekend specifically to layout what he calls 'foundational stones to mythtelling' - unmissable for any apprentice storytellers.

On the Saturday night an unexpected treat: we will be visiting the Wood Sisters Winter Storytelling festival in nearby Dartington where Martin will perform 'The Handless Maiden', and we will also witness the new storytelling Laureate of Great Britain, Katrice Horsley. Do not miss this juiciest of weekends - fellowship, laughter, stories shared, great food and wild possibility!

EMAIL tina. schoolofmyth@yahoo.com TODAY for place.

01364 653723 for more details

170 pounds (50 pounds non-refundable deposit), fully residential. More details on contact with Tina Birchill.

www.schoolofmyth.com

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)